Five feminist writers share their thoughts on what it means to empower women in Trump’s America.

A Chat With the Authors of “Nasty Women,” a New Book About Being Feminist in 2017

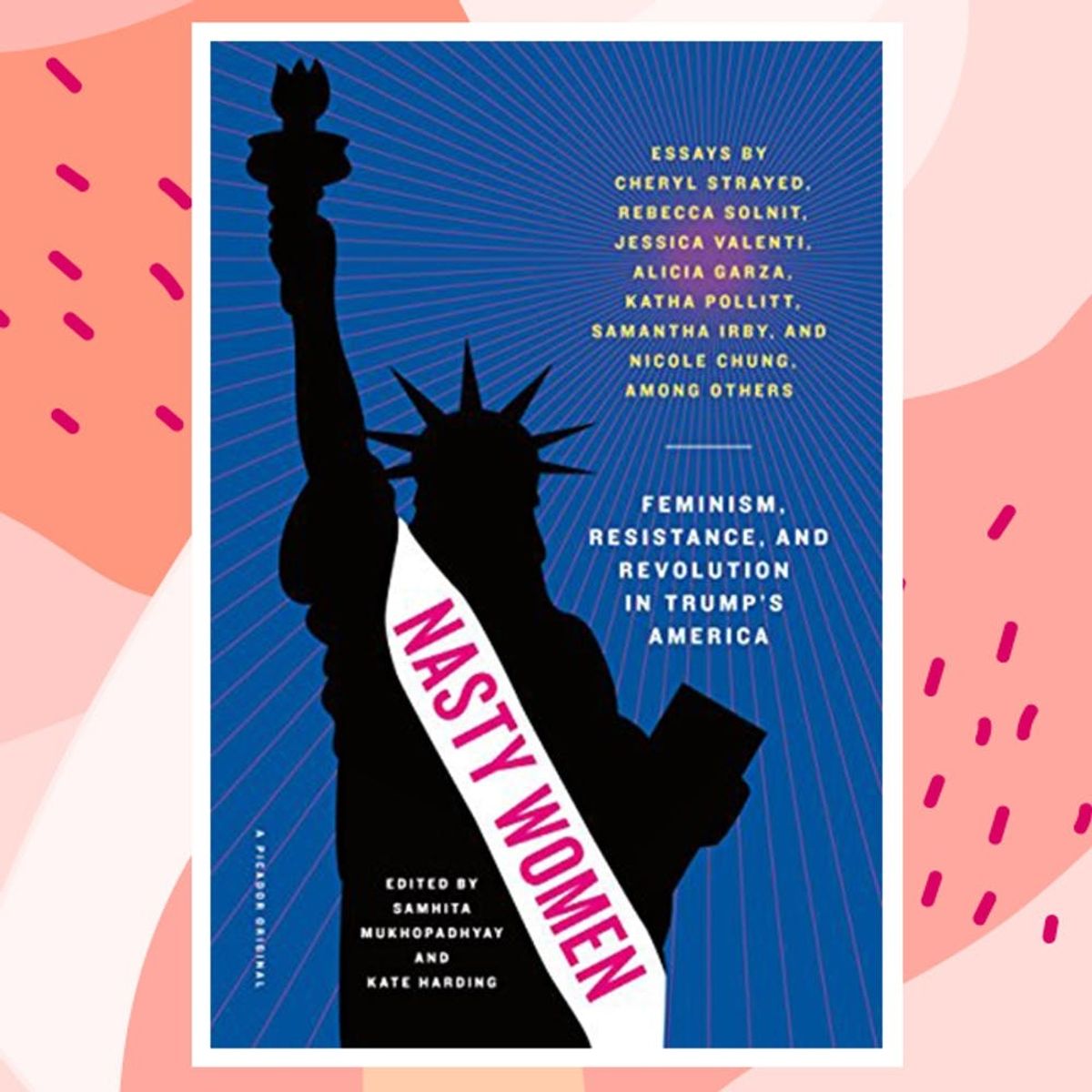

This week saw the release of Nasty Women: Feminism, Resistance, and Revolution in Trump’s America, an essay collection about feminism and politics by 23 prominent feminist writers, edited by Samhita Mukhopadhyay (Senior Editorial Director of Cultures and Identity at Mic) and Kate Harding (editor and author of Asking for It: The Alarming Rise of Rape Culture — And What We Can Do About It).

Almost one year out of the 2016 presidential election, the book couldn’t be more necessary. Each essay boldly explores issues like race, resistance, the pitfalls of white feminism, and ableism through the lens of its authors, who hail from varying backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives. And as a result, Nasty Women creates an important dissection of what it means to be a woman in a divided country in the wake of political and social turmoil.

We had a chance to have a conversation with Mukhopadhyay, Harding, and a few of the anthology’s writers about the realities of living in Trump’s America. We posed questions to Sady Doyle(writer and author of Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear . . . and Why), Collier Meyerson (journalist and producer), Kera Bolonik (writer and executive of DAME Magazine), and their editors about how their own politics changed in the wake of contributing to and editing the book, the tendency to pathologize the president, and how Nasty Women changed them.

ANNE T. DONAHUE: I was really fascinated by [Sady Doyle’s essay] “The Pathology of Donald Trump.” A lot of people seem to want to diagnose the president or to assess whether he’s psychologically fit for office. How do you think conversations about Trump’s mental health have helped or hindered a larger discourse about mental health?

COLLIER MEYERSON: Ironically, and thankfully, much of the current discourse around mental health seems to be in reaction to Donald Trump’s presidency. As opposed to it being focused on his mental (in)stability, it’s centered around how we (those of us who didn’t support his presidency and are negatively impacted by it) find ways to cope. Everyone I know — from people who are deeply involved in covering this political moment to those who are not particularly politically engaged — are having conversations about how to find moments of peace and respite.

SADY DOYLE:People saw Trump as “crazy” in part because he was villainous. We pathologized him in a way we might pathologize our crappy exes or our unfulfilling parents or whatever, just to have a name to call him. And yet, when you look at what’s on the chopping block in every repeal-and-replace effort, what is it? Mental health care. Medicaid. Things people with disabilities need.

This administration is actively harming people with mental illness in so many ways, and they’re able to get away with it because we still believe those illnesses are personal failings. If we only see “crazy” as “villainous,” we’ll spend all our time talking about Trump’s real or imagined pathologies, and none on how his administration is impacting people with mental illness and their access to care.

KERA BOLONIK: I have always struggled with depression; I’ve been in therapy for years, on medication, I take these things very seriously. But I’m in no position to put anyone on the couch, even if I do find myself thinking about Trump’s mental state. He lacks a basic humanity, empathy: Puerto Rico is devastated and he’s picking fights with the NFL. Apologizing that Melania couldn’t join him when she’s standing right next to him. He’s incoherent. Why, why is he like this? Why would anyone be like this?

I hate that there is way more discourse about Trump’s mental state than the state of mental health care in this country. And I don’t know that it’ll change anytime soon, but I hope that when he finally does leave office, our collective depression will lift, and we can have a meaningful discussion about how to restore and improve our health care — and our health — on every level.

Did writing the essays for this book change the way you talk about politics?

COLLIER MEYERSON: I think, like many women of color I know, I felt confused and a bit angered by the optics of the Women’s March, so writing the piece on the tension between women of color feminists and white women feminists in this moment was incredibly therapeutic. Intellectually, I wanted to have an uncomplicated connection to the Women’s March, to the largely white crowds of women marching. But viscerally, I was turned off, angered even.

Contending with those feelings was really important to my mental health. The essay helped me understand that I don’t necessarily need to feel resolved on how racism exists in feminism, that I’m constantly going to be navigating it, and that’s okay. It taught me that I don’t need to abandon feminism altogether but that I can hold space for my anger and resentment toward corporate, whitewashed feminism while also honoring the queer and POC-centered feminism that enriches my life.

KERA BOLONIK: Because I edit an online feminist magazine, I was already talking about politics before writing the essay, and I have to say, I am grateful for the ongoing dialogue I’ve been engaged in with the writers I work with because they really help me evolve, and in many instances, they’ve opened my eyes.

I remember a couple of years ago, one writer told me Trump would be elected, and I said, “Really? Isn’t he kind of like Sideshow Bob?” Because as a New Yorker, I’d seen him threaten to run for office, dip his toe in, and flee when he realized he didn’t have a chance. But that was my white-lady myopia talking. She said, “You are underestimating the racism in this country.” I didn’t entirely doubt it because we were seeing police murder Black men and women nearly every day. But I’d hoped voters were seeing what we were seeing and wanted it to stop.

As I mentioned in my essay [“Is There Ever a Right Time to Talk to Your Children About Fascism”], my mother had ingrained in my head that fascism never really goes away, it just lies dormant for awhile — and when things go bad, people look for a scapegoat, there’s a mob mentality, and people like to be told what to think and what to do. Everyone has forgotten to “never forget.” I think the difference in the way I write and talk about any of these things now is in the pitch — there’s more of a sense of urgency — because it’s not like any of these things are new, but Americans have been given license to say and do things they might not have before. And laws that protected us are being pulled out from under us. I’ve not been to so many rallies and protests since the late 1980s and 1990s.

KATE HARDING: Well, one thing for me is that I had a full-time job last year where I had to be circumspect about expressing my political beliefs. But as soon as Bannon was appointed, it was clear that all our worst fears about [white nationalism within] this government were well founded. I needed to be able to speak out about that in no uncertain terms, which meant I had to quit.

SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY: I literally pulled my hair out trying to toe the line of responsible journalist and political activist. I think that line is really blurry right now because this election felt personal in a new way (I take politics really personally anyway, but this took it to another level) and not expressing my terror or disdain felt disingenuous. So writing my essay and working on the book helped me ground myself in that rage and figure out productive ways to have these conversations rather than just being traumatized and spilling that trauma everywhere.

How did putting this book together evolve your own politics?

KATE HARDING: As an editor of this anthology, one of the things I was hoping to achieve was a version of what Collier’s talking about above: Demonstrating that there are a whole bunch of different angles on feminism under Trump, and we don’t have to be in perfect lockstep to mount an effective resistance. There doesn’t have to be — and could never be, honestly — a single Official Feminist point of view.

SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY: Working on the book forced me out of the day-to-day arguments within the left and to think more big picture: What do women need to read right now?

Have your thoughts about the situation changed since writing your essay for the book?

COLLIER MEYERSON: I wrote about the Women’s March, about the tensions between white feminists and feminists of color. And when I filed the piece I wondered if white cis women would show up for women of color, for immigrant women, for DACA recipients, when the shit hit the fan. After the Women’s March, when the administration’s policies started to really have an impact. And honestly, I don’t feel too different from when I wrote the piece. There is throwing up an Instagram post in support of NFL players taking a knee, in support of Puerto Rico, in support of DACA recipients, in support of trans men and women, and then there is doing actual work. I remain unconvinced that there has been some seismic shift in the way that middle class and affluent white cis women across the feminist board show up for women of color beyond symbolic gestures.

What did you realize you needed to change about yourself or your views as you wrote your pieces?

SADY DOYLE:Spending time engaging with the actual impact of mental health stigma reinforced how vital it was to talk about it — but I realized that if I wanted to do that, I couldn’t be too esoteric. And I was constantly pressing myself to write this in a way that I could explain in an elevator. I needed to welcome people into the conversation, and not just make the essay a demonstration of my own knowledge. I don’t know if I succeeded — someone else will have to read it and decide if it works for them — but that self-imposed pressure to be accessible is relatively new for me.

KATE HARDING: I need to be braver about working through what I really think about all of these issues, instead of just tossing another obvious take into the hopper. As an editor, reading all of these beautiful, vulnerable, sad, angry, frightened pieces was just an excellent reminder that listening to as many different people as possible is some of the most important work we can do.

SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY: It taught me to be confident in my vision and follow a hunch, which is how the book came to be — I knew women would have a lot of things to say that I alone wouldn’t be able to say. Imposter syndrome be gone! And also what Kate said: I alone don’t have all the answers and reading other people’s rage and experience is deeply humbling.

What truths has this book forced you to face? Whose writing gave you a perspective you hadn’t had yet?

COLLIER MEYERSON: That feminism won’t ever reconcile its race problem.

KATE HARDING: Until very recently, I’ve always had an America to believe in. Every time I realize that I don’t anymore, I hear Langston Hughes’s voice in my head: “America never was America to me.” I hope that more and more white feminists are waking up to what that really means every day, and that feminism as a whole keeps moving in the direction of centering the most marginalized women’s voices. I can’t say I blame Collier for being pessimistic about it, though.

This discussion has been edited for length and clarity.

What’s your take? Tell us your thoughts @BritandCo.

(Photos courtesy of authors. Illustration byYising Chou / Brit + Co)