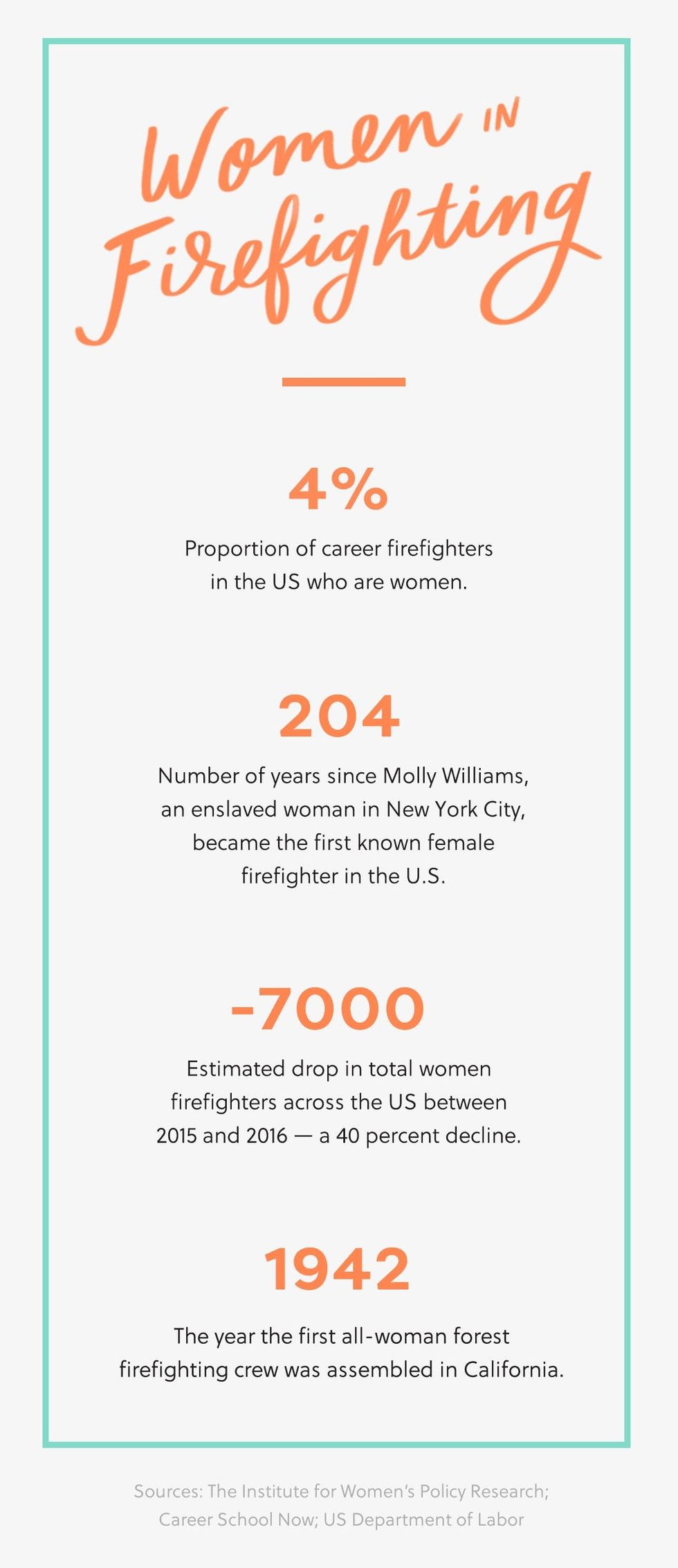

Only four percent of US firefighters are women. These women want to bring the change.

A Woman's Place: Women in Firefighting

A Woman's Place: Women in Firefighting

“A Woman’s Place” is a series spotlighting the women making bold moves in male-dominated industries.

Ali Rothrock knew she wanted to be a firefighter the moment she accidentally stumbled upon a fire station open house in the small town where she grew up.

“I walked out of church this Sunday and there was an open house thing in the center of town, and you can meet your community," the 29-year-old tells Brit + Co. Rothrock clearly remembers taking four steps into the firehouse when, as she tells it, "I stopped walking."

“It was like there had been a piece of me out there floating in the world that I was looking for, and when I stepped into that firehouse, and was standing in between these two giant fire trucks, it hit me in the face, like, ‘Oh, turns out I'm supposed to be a firefighter.’”

Rothrock acted on that feeling, and by the age of 21, she was a full-fledged firefighter in central Pennsylvania. But her dream job wasn’t what it seemed.

“The first firehouse where I started ended up being a place that was full of men who had one idea of who a woman firefighter can be,” she says. That idea was not, unfortunately, her.

“And it didn't matter that I was passionate, that I was confident, that I was capable, that I was there to learn from them. They just made it very clear that I was there to be quiet, I was there to look pretty, I was there to go along with all of the things that they said about me,” Rothrock adds. She describes that initial experience as “really, really traumatic.”

Although Rothrock has moved on from full-time fire work to the volunteer service in Pennsylvania, she’s used her experiences to shape her career as an author and full-time advocate for mental health support and inclusivity for women in the fire service.

AN UPHILL BATTLE

While women have made inroads in many male-dominated industries, women trying to enter or stay in the fire service continue to fight an uphill battle. Less than four percent of the firefighting workforce is female, and a Cornell University study from 2018 found that women firefighters simply aren’t getting hired. And while women have made some progress, it can be a struggle to achieve the same levels of success or respect as men entering the service.

For Sharon Purifoy, a fire captain and paramedic in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the fight to get accepted as a woman in firefighting started in the late 1990s. Purifoy had been working as a social worker when she realized she needed a change. On a whim, she took the written test required to enter the service. And although she passed the test, she wasn’t accepted into the service.

“Many of us took the test at that time,” she tells us, adding that she noticed that the majority of her fellow test-takers were visible minorities and women. “And [we] never got a call back, or we were placed really low on the list.”

In 2001, the Milwaukee Brotherhood of Firefighters — a professional network for African American firefighters — filed a complaint with the state’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, stating that anti-Black discrimination had played a role in the Milwaukee Fire Department’s disproportionate rejection of Black job applicants. The fight went to court, and a number of applicants who had previously been overlooked were invited to retake the test. Purifoy passed and officially signed on to the service in 2003.

“There are still guys in departments all over that feel that women just shouldn’t be on,” she tells us. “And unfortunately, you find a lot of women who feel like they just have something to prove. But I’ve never had that attitude because I thought, you know, the fire service needs to be inclusive.”

Although Milwaukee just celebrated its first all-woman fire crew — a crew Purifoy proudly served on — the city's fire department still has a long way to go where gender is concerned.

In 2017, several female cadets in the Milwaukee Fire Department filed complaints against male colleagues, citing sexually explicit name calling and harassment. Their action led to the firing of five male cadets — just one example of the industry-wide old-boys’ club mentality that threatens to keep women firefighters afraid to both speak up and climb through the ranks of the field.

Not every woman firefighter has a tough story to tell, though. Decatur, Georgia Battalion Chief Vera Morrison tells us that her career has been more or less smooth sailing — an experience she acknowledges is unfortunately not the norm. The 50-year-old mother of three openly wonders why it’s been so easy for her to ascend the ranks of her industry when so many of her women colleagues haven’t fared so luckily.

“I will tell you this: Not every female in the fire service has had the same experience that I have had,” she tells us. “And I have heard the horror stories and it breaks my heart, and I wonder, did I do something that made people feel like they couldn't treat me that way? Or did I do something else that made them say, ‘Oh, you know, she is one of us.’”

From fire station setups that are designed only to accommodate men, to a lack of private bathroom facilities for women, to grooming policies that center on men’s hairstyles, to even the sizing on protective gear and uniforms, women firefighters often face gender-related barriers that extend well beyond matters of harassment and intimidation. In fact, according to the i-Women national survey of women firefighters, 80 percent of respondents reported ill-fitting gear, and 68 percent reported no discrimination complaint filing processes in their workplaces.

Even the hiring processes for women in firefighting can be discriminatory, as some of the women we spoke to admitted. Women, in general, tend have a harder time building upper body strength than men; our power tends to reside in our legs. For a top-heavy lifting job, this can be problematic, and fire testing and training don’t account for that.

Morrison worries that there are prospective women firefighters who are being disqualified from service before they’re given a proper chance to adapt to the new demands of the job. “It’s still hard for women to get on the fire service,” she says. “And they think that we're saying [they should] make the test easier, but I'm saying if I've never climbed a 110-foot ladder in my life, don't fail me and say that I can't be a part of the service because I haven't learned to climb that ladder yet.”

HOPE FOR THE FUTURE

But for all the hurdles, the women we spoke to all agreed that they never would imagine their careers anywhere else. Binghamton, New York firefighter and paramedic Bethany Matias tells us that because she’s always recognized that she’d be outnumbered as a woman in her chosen career, she’s taken challenges in stride.

“I've never paid attention to [gender bias],” she says. She also tells us that most of her gender-related interactions have come from the public while on call, not from her male colleagues. She’s nonchalant when she explains that, yes, sometimes people are surprised to see a firefighter who also happens to be a woman. “And it's not a bad thing, it's just that, ‘Oh, I didn't know there were any women on the department!’” she tells us.

Matias also notes that any gendered pushback she has received at work has tended to come from older men on the job. She doesn’t take it personally — in most instances, she’s been able to chalk up certain behaviors to her coworkers' ingrained ideas about the roles of men and women, and not about her as a colleague.

“They kind of, without thinking about it, still grab the door for me,” she says. “Or they don't want me to pick up something heavy, but they don't realize, and they're just like, ‘Oh, yeah, sorry.’”

The younger male firefighters coming into the industry have a different attitude. “Some of the younger guys just treat me like I'm their sister,” she notes. “I work side-by-side with them. I have never encountered any problems.”

Morrison, Purifoy, and Matias all say similar things: Although there are struggles right now for many women in the service, they all see a better future for women, which, in turn, will make the industry better as a whole.

“Our job is so dangerous, it doesn't matter what happens at the end of the day,” Morrison says. “We have to depend on each other. Because I want to go home the same way you want to go home. And as long as that is understood, everything outside of that is irrelevant.”

(Design by Marisa Kumtong + Casey Callahan / Brit + Co)