These women are working hard to crack the glass ceiling of the aerospace industry, once and for all.

A Woman's Place: Women in Aerospace

A Woman's Place: Women in Aerospace

“A Woman’s Place” is a series spotlighting the women making bold moves in male-dominated industries.

When NASA was preparing to send the first American woman into space, the agency's men had a few pressing questions. Specifically, what would happen when Sally Ride got a visit from Aunt Flo in low-earth orbit? (Theories ranged from "nothing" to "possible death.") Would a hundred tampons be enough to get her through the week?

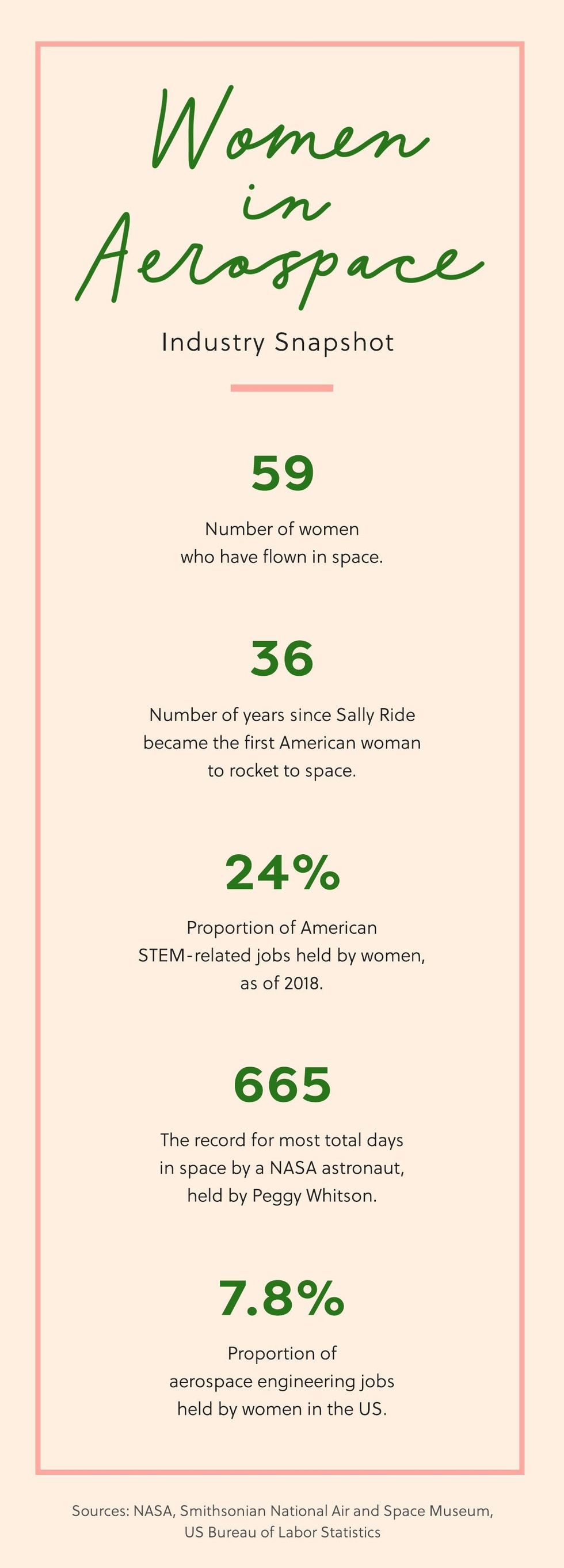

Women have been flying in space since the 1960s, when Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova spent nearly three days in orbit in June 1963. But space-faring women didn't really get off the ground until NASA opened its doors to women in the late 1970s. Since Sally Ride's historic 1983 space mission, 46 American women — and 15 more from other countries, including Great Britain, India, Israel, and Canada — have all orbited.

Women have been shuttle commanders and payload specialists, helped construct the International Space Station and operate the robotic arm (known fondly as the Canadarm), and logged thousands of hours in space and in training programs. On the ground, female engineers have worked on missions and designed hardware and software that have been essential to space exploration.

Women have been involved since the very beginning, but you only need to watch Hidden Figures to see how their stories have often been squashed, ignored, or forgotten. And now, as America considers returning to the moon and venturing onto Mars, leaving women out of past, present, and future space exploration may have serious research implications. Does space have a glass ceiling?

IN THE BEGINNING

In America, the so-called Mercury 13 program was created by William Randolph Lovelace II. Lovelace helped design the tests given to some of the first astronaut trainees as part of NASA's Mercury Program, which ultimately launched Alan Shepard into space in 1961. Lovelace was interested in the question of how women would perform in space, and approached Geraldyn "Jerrie" Cobb, an experienced pilot, to help find the answers.

Lovelace and Cobb looked at more than 700 female pilots, each with at least 1000 hours of flight experience, and selected 19 women to become what Cobb dubbed the First Lady Astronaut Trainees, or FLATs. Those 19 women, alone or in pairs, were subject to the same tests that the male astronauts received, such as x-rays and physical exams. But they also received much more rigorous testing: Ice water was shot into their ears to induce vertigo, and then they were timed to determine how quickly they recovered. They received electric shocks to check their reflexes. Their stomach acid was retrieved through a tube and tested. Of the 19 women in the program, 13 passed all the tests in Phase I.

Lovelace's theory was that women, typically smaller and lighter than their male counterparts — and therefore less expensive to launch into space — would also be better able than men to cope with isolation and would have better cardiopulmonary function. His experiments checked out, and he arranged for Phase II of his three-part testing to take place at the Naval School of Aviation Medicine in Pensacola, Florida. Days before Phase II was scheduled to begin, the testing was canceled: NASA didn't condone the program, and the US Navy wouldn't let Cobb and Lovelace in without its approval. Cobb, as Lovelace's initial test subject, had completed all three phases of training, and her stats placed her in the top two percent of astronaut candidates. She never flew in space.

At the time, astronaut trainees needed to have graduated from a military jet pilot program and have a master's degree in engineering. Women, being barred from American service academies until 1976, were thus ineligible. However, things started to shift in the late 1970s and early 1980s, for several reasons. Women gained admission into service academies, which meant they could earn military flight credentials. NASA was developing the Space Shuttle program, which opened roles for non-military crew. There was also more legislation in place to protect women against gender-based discrimination. In 1978, NASA selected the Astronaut Group 8 — ironically, nicknamed "Thirty-Five New Guys" — which included, for the first time ever, five women.

BOOT CAMP

"I wish it was it was a unique story, but when you talk to astronauts who are around my age, we can tell you exactly where we were when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon for the first time," astronaut Wendy Lawrence tells Brit + Co by phone from her home in Colorado. She laughs, and adds, "We were right in front of our televisions at home, and I can't actually put it into words."

Lawrence was 10 years old when Aldrin and Armstrong walked on the moon, and those broadcasts left an indelible mark on her childhood: "That's the day the dream began."

Lawrence, who went on to fly on four space shuttle missions between 1995 and 2005, grew up surrounded by servicemen: Both her father and her maternal grandfather attended the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. When Lawrence decided that she wanted to become an astronaut, she followed in their footsteps.

"Knowing that a lot of astronauts had gone to the naval academy, had been in the military, had been pilots, that was the next step after high school," she tells us.

Lawrence was part of only the second class at the academy to admit women. During her first summer at the Naval Academy, she recalls that "there were literally people there, touring around the grounds, who would line up on the sidewalk because they were looking for one of those 'female midshipman.' And as we'd march around, we'd hear, 'Oh, there goes one!' And we, the women, did not want to be singled out that way."

Lawrence eventually became a helicopter pilot and then the first female Naval Academy grad to go to space — one of only a few dozen women among the Academy's 4,500 students.

When she joined NASA in 1992, Lawrence found a very different environment. "First off, many more women. Many, many more." She estimates that nearly 30 percent of the astronaut corps at that time was female. "And women were working across the space center," she adds. "They were in the engineering directorates, they were in the other aspects of the space shuttle program, they were flight controllers, they were training us."

Lawrence flew with other female astronauts, including Tamara Jernigan and Eileen Collins. However, her missions never achieved gender parity; the closest she came was a flight with two other female astronauts, on a crew of seven astronauts total.

GROUND CONTROL

When Terri Taylor first started working, people used to call her "sunshine" — much to her displeasure. "I always thought that was so insulting," she says.

Taylor is now a Senior Technical Manager with Honeywell Aerospace, where she developed a cleaning process for space-bound spin bearings. Her work has been used on the International Space Station and the Iridium NEXT telecommunications satellites, among other projects. She tells us that she became interested in engineering because of a childhood love of science-fiction novels.

Taylor has been working at Honeywell for 29 of her 36 years as an engineer. When she entered the field, things were very different for women. Taylor recalls that she had no female role models when she was starting out — "I was the only female engineer in the department" — and when asked if she was lonely, she laughs.

Over the years, however, Honeywell has made a real effort to recruit more women, and Taylor says that it shows. "There has definitely been a shift, certainly in the numbers. The number of women in the engineering workforce have definitely increased," she tells us.

But Taylor's optimism is tempered by the knowledge that just getting into the field can still be tough for women. "There are so many barriers that have been broken, but the biggest challenge would be the first step in the door. If you're interviewing with a panel of all men, it's still a challenge."

Men outnumber women by a factor of six to one in engineering, and while women are enrolling in STEM degrees at higher rates than ever before, they are still underrepresented in computer science and engineering. Taylor thinks it's a shame, given how much women have to offer.

"Women are very good being focused and getting things done," she tells us. "I've worked with a lot of very driven women who know how to get things done. Not that the men don't, but the women bring a different flavor."

A DIFFERENT FLAVOR

That different flavor is at the heart of the diversity drive in space and aeronautics. Nearly everyone we spoke with mentioned the value of different perspectives to the industry as a whole. Janet Sellars, the Director of Diversity and Data Analytics at NASA in Washington, DC, says, "Diversity in general improves your solution set all the way around." And for an agency devoted to solving that pesky gravity problem, that's a strong motivator.

However, women are still underrepresented at the agency. Of NASA's 17,227 employees, 5,884 are women; 2,606 of its 10,711 science and engineering staff are women. However, Sellars remains upbeat.

"While our participation rate in the workforce has remained relatively steady, more women are getting promoted to higher levels, and more women are staying longer," she tells us. "Even though we may not see huge numbers in terms of representation, the women that are here are getting high levels, high visibility assignments, and they're staying much longer." As an example, Holly Ridings was recently named the first female chief light director for NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, and is now tasked with managing all the human space flight up the ISS. Ridings has been with the NASA for 20 years.

Tracy Drain works out of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. She joined JPL fresh out of school 18 years ago. Previous assignments have included the Juno mission to Jupiter, and Kepler, a planet-finding mission, but since 2017, she's been the Deputy Project Systems Engineer for the Psyche asteroid mission, which NASA has dubbed "Journey to a Metal World." In her role, she acts as a bridge between different teams: "On a spacecraft, you might have people who are very knowledgeable about thermal and power and telecom, all of those different areas. A systems engineer's job is to make sure that we don't make choices in one area that makes the design a lot harder or even dangerous in another area."

Drain says NASA's engineering-driven culture allows for a level of bluntness that might be unfamiliar in other settings. "Because we're all used to working on technical issues where everyone has to be above-board about all of their thoughts — because if you aren't, you could miss something that ends up killing the mission — we're used to very open, collaborative conversations where people try their best not to overly sugarcoat things."

This straight-talk mindset extends to conversations about diversity in the workplace. "It's nice to not have people who all went to the same school, and all trained in engineering in the same way, and who all grew up in same country," she tells us.

But Drain admits that, as a Black woman, she sometimes faces added pressure to be a trailblazer. "They're really trying to make paths for women in leadership roles, so they can change the way that whole upper echelon looks," she says. "These are some of the conversations that I've had with other women, especially women of color. There's that double pressure. They want more people who are minorities, and we also want more women as well: You check both those boxes!"

Drain also believes that women in her field may feel the need to tread more carefully than their male colleagues, to "make a choice in a certain way, for the good of other people, as opposed to just doing what [we] want to do." She laughs, then adds, "For the most part, men don't have that added pressure. It would be nice if we get to the point where we have [gender] parity so nobody has to worry about that."

MEN BEING ALLIES

NASA, which has been ranked at the top of the Best Places to Work survey of federal agencies for seven years running, offers employee resource groups and affinity groups for women at its 10 campuses around the country. "There are a lot of men active in those groups as well. They want to be allies," Sellars tells us.

Shelli Brunswick is also a proponent of male allies in aerospace. She's the chair of Women In Aerospace (WIA) and the COO of The Space Foundation. "My mentors were men who could mentor me and guide me in my career," she tells us by phone. "They saw a talent in me and helped make sure I wound up of the right place."

Brunswick, who spent 29 years in the military, became involved with WIA when a (male) colleague asked if she was a member; she had never heard of the group, but her curiosity was piqued. She joined the WIA board in 2014.

"It's not a woman-only organization," she explains. "Being part of the solution requires everyone to be part of the team, which includes men. If you're talking about diversity, it requires everybody to be in the conversation."

The Space Foundation recently launched a diversity initiative called Space Commerce, designed to attract minorities to space commercialization ventures. Brunswick sees her work at WIA and The Space Foundation as a way of giving back.

"All the women who are where they are today, are because of those who came before us. I'm standing on the shoulders of others, who have pioneered their way," she tells us. "The first female fighter pilot, first female astronaut — I'm benefitting from their struggles."

Brunswick isn't alone in this view. Throughout our conversations with women aerospace professionals, a give-back attitude was prevalent. Mentors and role models, female friends, and encouraging family members made a big difference; so did supportive work environments that made an effort to include and promote women. Working on space-related projects has been a professional launching pad for many women — and opened the door for many more. After all, as Brunswick points out, "Nobody goes to space by themselves."

(Written by Kaitlyn Kochany. Design by Marisa Kumtong/Brit + Co)