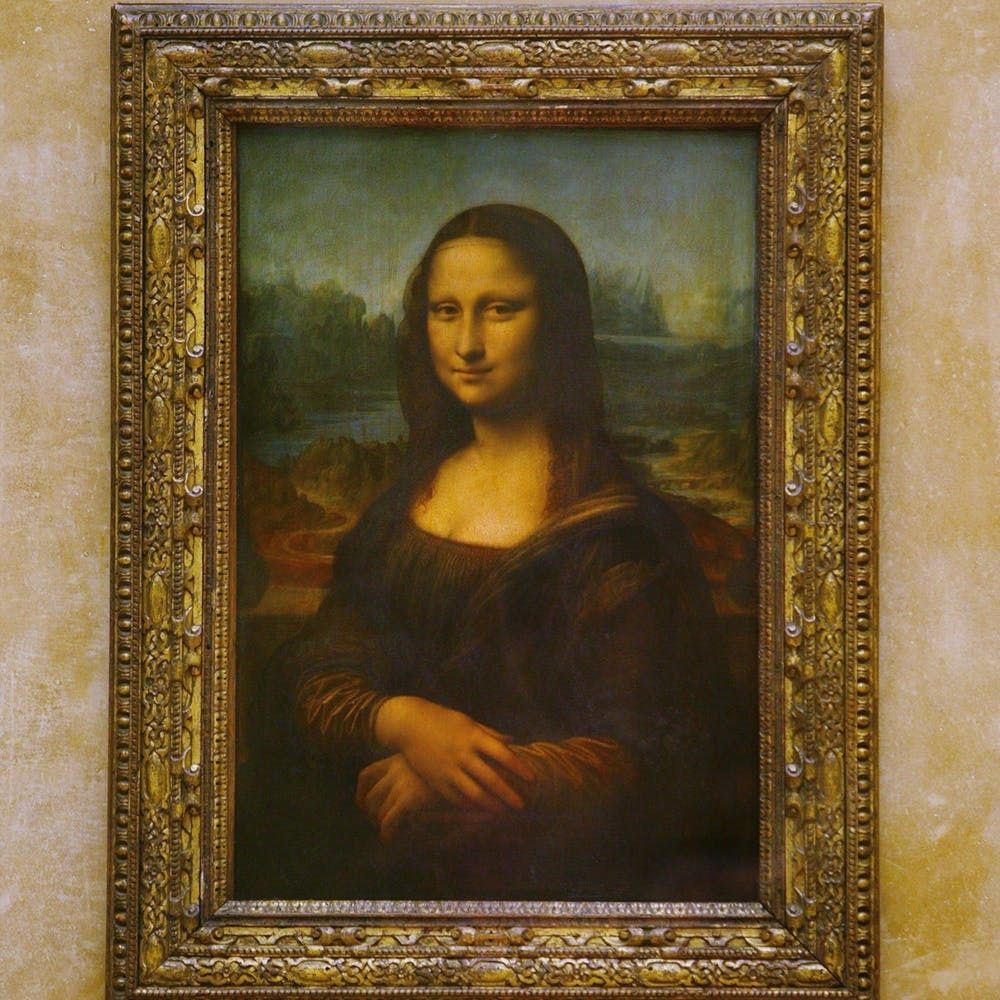

One of the world’s most adored pieces of art, Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” draws thousands of travel lovers to the Louvre Museum in Paris every day. (Thanks to these cheap flights to Europe, it’s never been easier to head overseas!) The well-known 16th-century oil painting is equally captivating and mysterious, thanks to the subject’s totally ambiguous expression. Though historians, artists, and pop culture experts have long tried to figure out what her smile actually says, a recent study published in Scientific Reports shows that many people think she looks happy.

The study, conducted at the University of Freiburg, asked 12 people (five men and seven women) between the ages of 20-33 to view the original “Mona Lisa” plus eight slightly edited versions, each one showing subtle changes to the curvature of her mouth. The researchers showed each participant four “sadder” versions of the original painting and four “happier” versions in random order 30 times. The participants then recorded their perception of the image — whether they thought it was happy, sad, or neutral — and rated how confident they were with their answers.

Surprisingly, nearly 100 percent of the study’s participants ID’ed Mona Lisa’s expression in the original painting as “happy.” Plus, respondents were able to identify the “happier” images faster and with more confidence than the “sadder” images. Emanuela Liaci, a PhD student and one of the study’s authors, explained this finding, saying that the human brain might “be more biased to positive facial expressions.”

A second experiment dug a little deeper into how we perceive images. It showed that our emotional assessment of an image actually depends on context. For this experiment, the same team of researchers showed participants the original “Mona Lisa” plus seven other “sadder” versions of the image, which included three images from the first experiment.

The researchers had some surprising findings: Participants thought the *same* images from the first experiment appeared to be sadder in the second experiment — that is, when shown in a group of images that had less happy expressions overall. Dr. Jürgen Kornmeier, a lead author of the study, says, “The data show that our perception, for instance, of whether something is sad or happy, is not absolute but adapts to the environment with astonishing speed.” Wow.

Dr. Kornmeier adds, “Our senses have only access to a limited part of the information from our environment, for instance, because an object is partially hidden or poorly illuminated.” He explains that the brain uses this sensory info, though restricted or vague, to “construct an image of the world that comes as close to reality as possible.” In other words, happiness — just like beauty — is in the eye of the beholder.

Do you see the Mona Lisa as being happy or sad? Sound off on Twitter @BritandCo!

(Photo via Raphael Gaillarde/Getty)