A Woman's Place: Women in Coaching

“A Woman’s Place” is a new series spotlighting the women making bold moves in male-dominated industries.

“I came from a family of lawyers,” says Lindsay Gottlieb, the head coach for the University of California, Berkeley women’s basketball team. “Our dinner table conversations were either about somebody’s case that they were working on or about sports. That’s just what our family did.”

Though her brother and sister both headed into the legal profession, Gottlieb poured herself into college basketball and began her coaching career immediately after graduating from Brown University in 1999. Despite straying from the family business, Gottlieb recalls the pride of her late father — then a respected civil court judge in Queens, New York — in her decision to follow her athletic dreams.

“I’d go to his courtroom — you know, he’s friends with all the stenographers and all the court attorneys — and they’d all say, even though my sister’s an attorney and my brother is a law professor, they’d say, ‘He talks about your job the most,’” she tells us.

While Gottlieb has found a lifelong career coaching elite women at the university level, she, along with a handful of women peers, are outliers in their profession. Throughout every major sports league, there are exactly zero women who coach men at the head coach level. Zero. None. Men make up the majority of coaches at both the college and professional level in even women’s sports, and outside of a few exceptions in assistant positions, men’s sports don’t seem to welcome women in coaching.

But a change may be on the horizon. In May 2018, 41-year-old Becky Hammon made headlines as the first woman ever to interview for a head coach position in the NBA. Four years earlier, she was hired as an assistant coach for the San Antonio Spurs and became the first woman to hold that position across the league. Though Hammon did not end up being picked as head coach for the up-and-coming Milwaukee Bucks, it seems likely that she’ll get another shot at a head coaching role in the future. If someone like Becky Hammon can rise to the top, maybe the whole coaching industry is ready for a shake-up.

While we may be quick to assume that sexism is the underlying cause for the lack of women in head coaching positions, the reality might be more complicated. According to some reports, the law that made postsecondary education more accessible for women in the US may be partly to blame for so few women being invited to coach professionally in the first place. Understanding that history may also help us recognize how and why we might reverse its unintended side effects.

Title IX

In 1972, the gender equity law Title IXwas enacted to protect women from sexist discrimination in publicly funded colleges and universities. It stated that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

While Title IX opened up educational and career opportunities for many women, it also allowed more women to choose careers in mixed-gender settings instead of settling into work that had always been readily accessible — which, before Title IX, included coaching.

Before Title IX, women coached 90 percent of women’s college teams. Today, slightly more than 40 percent of college-level coaches are women, and that lack of diversity funnels into professional sports as well.

According to the NCAA, fewer than three percent of professional coaches are women, and their bosses, the athletic directors, are men in eight out of 10 sports organizations. But 34-year-old soccer coach Kati Jo Spisak senses that there’s a shift coming, even if the impact is slow to hit the mainstream.

In addition to her head coach position for the Washington Spirit Reserves women's soccer team, and her assistant coach position for its pro league counterpart Washington Spirit, Spisak is an associate athletic director at a private girls’ K-12 school in Maryland.

“I see more women as athletic directors now,” she says, “and I don’t know if that’s a shift in society, but I think that shows that as we get more females in leadership positions, [as] it becomes a norm, you won’t think twice [about seeing women coaches].”

A Different Kind of Coach

As coach and Basketball Hall of Fame athlete Nancy Lieberman sees it, women often bring a style of coaching that is better suited to today’s athletes than the stereotypical, hot-headed male coach of the past.

“Athletes are human beings and sometimes behind all our bravado, we’re just kids and we’ve been in a situation where we have to act like we know it all,” she says. “I believe that today’s athletes, you have to really — it’s like parenting. And I think if you’re [thinking like] a parent, you’ll be a better coach. Because if you’re a parent, you understand human nature.”

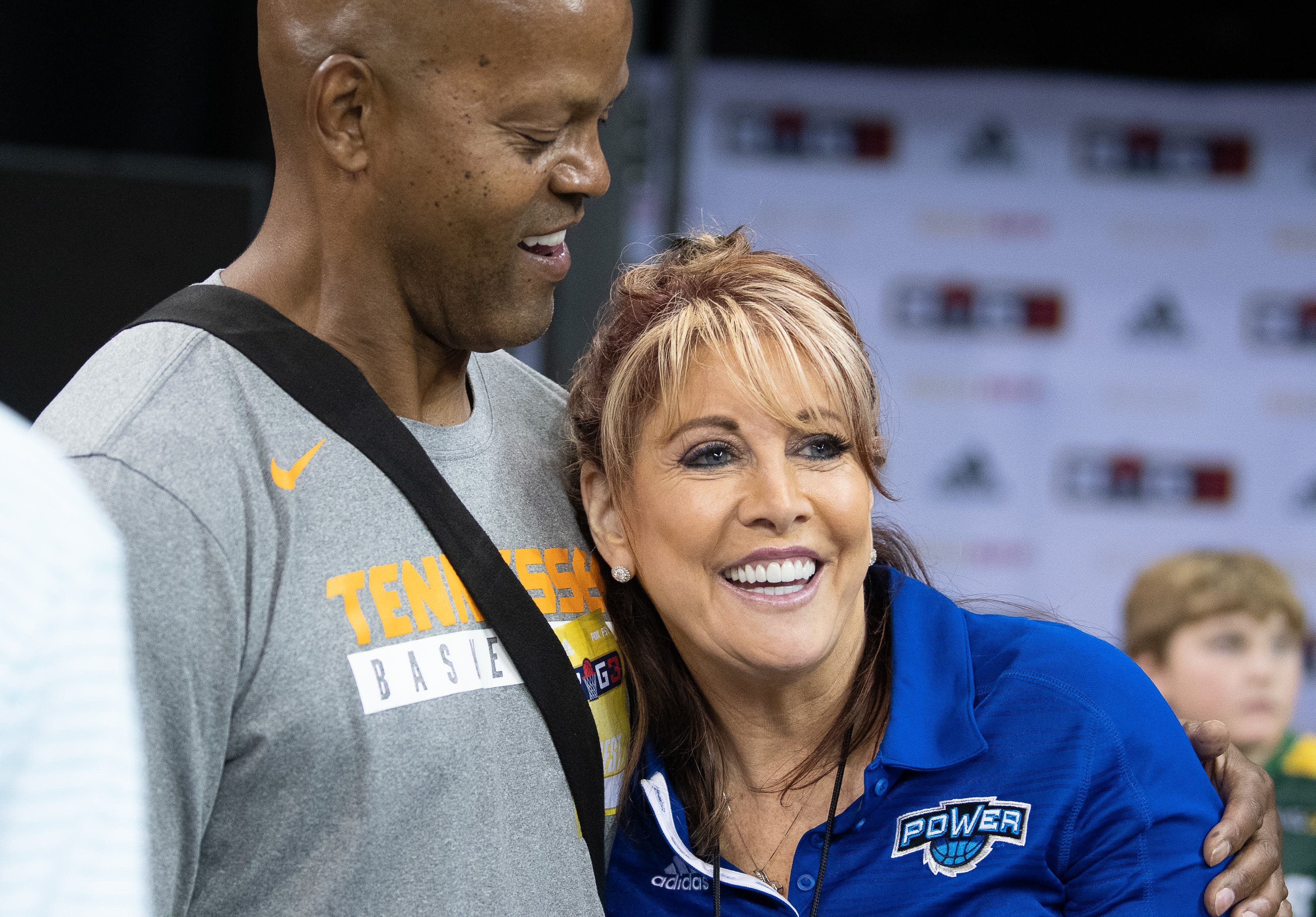

Lieberman, now 60, has had lots of time on the court to ponder human nature, too. Nicknamed Lady Magic when she started her professional career as a teen athlete, Lieberman became the youngest player ever to win an Olympic medal when the US women’s basketball team took silver at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. In 2009, Lieberman was named head coach of the Dallas Mavericks development team, the Texas Legends, and became the first woman coach of a professional men’s basketball team. In 2015, she was named an assistant coach for the Sacramento Kings. Most recently, in 2018, Lieberman earned the head coach title for the BIG3 basketball team Power, a three-on-three team comprised mostly of retired NBA players.

Lieberman has the prestige and life experience to know that, as a woman in a male-dominated industry, it’s not enough to know how to coach “like a parent.” She, and all the other women coaches we spoke with, are adamant that they have to be that much better than their male counterparts in order to reach the same pinnacles in their careers.

“We have to earn the right and work hard. We can’t be just as good; we have to be better than the person we’re competing with,” explains Lieberman. “But the men have shared this with one another for so long [and] are so good about sharing, that we need more women connecting at the next level.”

It’s About Relationships

Perhaps it’s a uniquely feminine perspective that led each of the coaches we spoke with to emphasize how the interpersonal relationships they have built over the years helped define their career trajectories — relationships that not only helped to secure their current jobs but also gave them the experience they needed to thrive along the way.

Gottlieb cites a friendship with Golden State Warriors head coach Steve Kerr, who invites her to his team’s practices to give her some insight as to how his team operates. Lieberman recalls similar experiences throughout her career and says she’s grateful for each connection she’s made.

“To be able to coach on that next level, NBA whatever, it’s all relational,” she explains. “You do not get jobs here on resumes. You get it on somebody who knows you and your work ethic and your character and knows you can do what you say you can. And that’s the secret sauce.”

Lieberman credits her friendship with legendary NBA commissioner David Stern for even getting into coaching on the men’s side. She says a fortuitous meeting with her friend, where he explained what the NBA Coaches Symposium was and why she should attend, changed her whole career — even though it meant missing out on her own Basketball Hall of Fame induction.

“‘Nancy, you need to go to LA to the NBA coaches symposium,’” she recalls him telling her. “And I say, ‘What’s that?’ He says, ‘You need to be where people are gonna hire you and get to know you.’ And I’m like, ‘But I have to go to the Hall of Fame, I’m a Hall of Famer.’ And he goes, ‘That’s who you were. Who you are is a basketball coach, and you have to be around the people who will hire you.’”

Where Women Are Going

There are plenty of reasons why women coaches are needed for both genders, at all levels of sports. For one, kids who don’t get an opportunity to be coached by women are likelier to believe that sports are a man’s world, and the cycle of keeping women out of professional coaching positions begins anew, pushing girls out of athletics altogether. In fact, by the age of 14, girls leave competitive sports at twice the rate of boys, and that’s due, in part, to the lack of women in leadership roles. According to the Women’s Sports Foundation, girls’ dropout rates are directly related to lack of equipment, lack of support, and a lack of women coaches.

“Girls respond well to female coaches, and good coaches keep kids in sports,” Risa Isard, the senior program associate at the Aspen Sports & Society Program, told The Atlantic. Lieberman agrees.

“Yes, we have to invest more in women’s coaching, yes, we have to create more relationships, and yes, former players have to be fans of the game,” she says.

And while women work on supporting each other, Gottlieb feels that the overall cultural shift away from old-school, sexist perceptions of a woman’s ability on the court will only help to get more women into positions where they will be able to take control of their teams and thrive.

“I’ve coached some young women who are now [in] coaching themselves, I’ve hired women that I’ve coached in internship positions and assistant coaching roles, and to see them go off to get jobs is really neat,” she says.

Gottlieb recalls a conversation she had last year with one of her freshman players, a “really smart” student who was taking courses in business analytics and statistics at the time. “She wants to be a GM in the NBA because she knows this analytics stuff,” says Gottlieb. “And I said, that’s the way the front office in the NBA is going — lots of smart people who know analytics. And it’s funny, both of us said, sort of at the same time, that by the time she becomes a GM, hopefully, she won’t be the first one [who’s a woman].”

Spisak is also excited to see what the future will hold now that talent and ability are truly starting to trump gender in professional sports.

“The cool thing is that knowledge of a subject, [that] doesn’t discriminate on gender,” Spisak concludes. “And, at the end of the day, if we focus on education and helping get more women into sports early on, we can keep shifting towards that equality and allow more women to flourish in professional sports.”

(Illustrations by Sarah Tate/Brit + Co)