Meet a handful of women making a career out of the mountains.

A Woman's Place: Women in Rock Climbing and Mountaineering

A Woman's Place: Women in Rock Climbing and Mountaineering

On a snowy November day in 1981, Kitty Calhoun found herself slipping into hypothermia near the summit of Mount Washington, the highest peak in the Northeastern United States. At the time, Calhoun was a senior at the University of Vermont and still a rookie alpinist. She and a friend had decided to ascend a 23-mile Presidential Traverse route in a single push, bringing only food, water, and sleeping bags. Despite its relatively modest height of 6,288 feet, Mount Washington's peak remains both revered and feared by even the most experienced climbers for its volatile weather conditions. Since 1849, the mountain has claimed more than 150 lives, and 28 of those deaths have been attributed to hypothermia.

"I was shivering cold," Calhoun recalls to us. "I started doing jumping jacks and that still didn't warm me up. I was a little bit frightened for a second and then I had a Snickers bar and I got warm right away."

The close call was one of Calhoun's first lessons in the unrelenting and often harsh realities one must face when making a career out of the mountains. Ultimately though, the dicey experience didn't deter Calhoun from the outdoors so much as it plunged her further into the arms of the wilderness. "That's when I became intrigued with alpine climbing," Calhoun recalls. "There are all these different uncertainties you have to try to figure out. It's like a chess game."

After 38 years of mountain guiding, Kitty Calhoun has become something of a legend in the mountaineering world. She is the first woman to summit the highly technical West Pillar route of Makalu, the world's fifth-highest peak, and the first American woman to ascend Dhaulagiri, a 26,795-foot-tall mountain in Nepal.

Even over the phone, 2,000 miles away, Calhoun's impenetrable sense of determination comes through as clearly as her trademark southern drawl. As she reminisces over her early years as an ice climber, there is a sense that — despite being a pioneer in the sport — Calhoun never spent much time dwelling on the hardships that may come with being one of the few women frequenting high-altitude peaks. That's not to say she was oblivious about them; she was simply too focused on climbing to pay any of that much mind.

"Whenever I felt like somebody was questioning whether I was capable, I didn't say anything," she says. "I just let my actions speak for themselves. It didn't take long for people to realize that I knew what I was doing and I was just as capable as they are — if not more so."

Calhoun's almost superhuman drive has served her well in the predominantly male world of mountaineering, but she still understands the importance of chiseling out space so that more women can follow her lead. In 1999, she became the first alpine guide for Chicks Climbing and Skiing (formerly known as Chicks with Picks), an outdoor adventure company that offers a variety of clinics for women interested in ice climbing, skiing, and various other backcountry skills. Three years ago, she became a part-owner of the business.

After a highly accomplished career, the now-58-year-old Calhoun has reached a point where she sometimes questions if she still has it in her to square up to the big mountains. She recalls the last expedition she went on: "I went on that trip thinking, 'I'm gonna give it all I've got, but I don't know if this is still me or not. If it's not, I'm okay with that.' But I walked away thinking, 'Man, this was one of the greatest times of my life.' I think I'll know when I'm done, but I don't think I'm done yet."

IT'S LONELY AT THE TOP

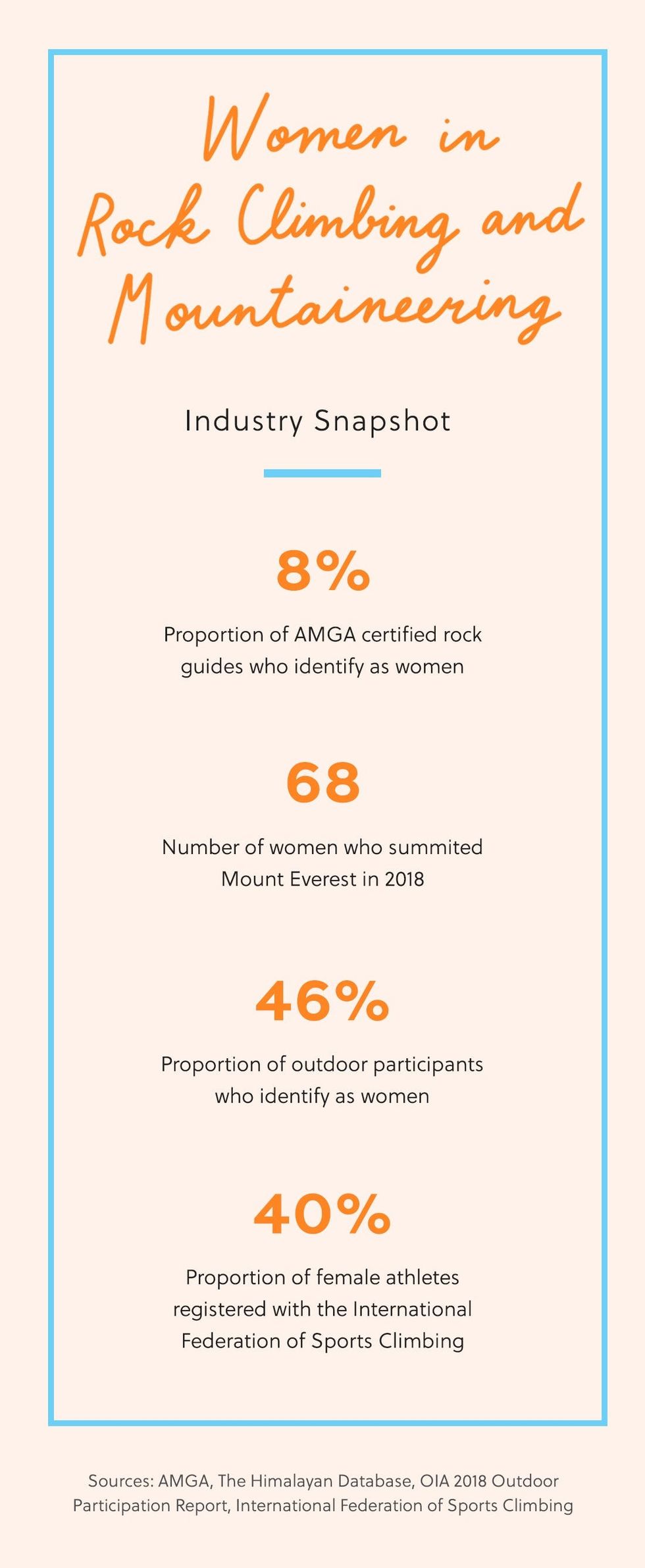

Despite its nearly two centuries as a sport, mountaineering remains a relatively small professional field, largely because its barrier to entry is so high. For alpinists who are not sponsored or certified-professional guides, getting into the sport can be both expensive and time-intensive. (A guided expedition on Mount Everest typically costs about $45,000 and takes upwards of 60 days to complete.) Nearly 99 percent of first ascents thus far have been made by men. Even still today, only eight percent of guides certified by the American Mountain Guide Association are women.

Closer to the ground, a different scenario plays out. The world of climbing is currently seeing an unprecedented surge in popularity, both overall and specifically among women, largely thanks to the rise of indoor climbing gyms. According to Climbing, an estimated 450 gyms are now open for business across the country. These facilities offer a unique opportunity for people to learn an outdoor skill without requiring access to a mentor or a remote location. For those with a climbing gym in their city, a day pass and some rental shoes are all that's needed to give rock climbing a try. The climbing gym is a natural gateway to eventually venturing onto a real rock and maybe even pursuing the sport professionally.

It should be noted that while climbing and mountaineering are inextricably linked, one is not necessarily synonymous with the other. Mountaineering is the oldest and most adventurous climbing-related recreational activity. It typically includes a combination of rock climbing, ice climbing, hiking, map orienteering, and sometimes even skiing. Mountaineers and alpinists are mainly focused on summiting gargantuan peaks, some of which can take weeks, if not months, to complete. In climbing (which is often segmented into sport climbing, traditional climbing, and bouldering), the objective is to get to the top of a specific boulder or mountain face (commonly referred to as a "problem"). Depending on the problem, climbs are typically completed in anywhere from minutes to hours.

Because of climbing's increased accessibility, a record number of women are taking up the sport. Forty percent of the licensed athletes currently registered with the International Federation of Sports Climbing are women. As female representation grows, so do women's accomplishments in the field. In 2016, at just 14 years old, climbing prodigy Ashima Shiraishi successfully sent (read: completed) the hardest boulder climb ever done by a woman. In 2017, 20-year-old Margo Hayes shattered a glass ceiling twice in the same year when she became the first woman to send two confirmed 5.15a climbing routes. There is a lot of insider vernacular involved in recording historic climbing feats, but all of this is to say: Women are proving themselves not just capable but quantifiably excellent at climbing mountains.

LEADING THE PACK

While the statistics look promising, the climbing community still has room for cultural improvements. In 2016, Flash Foxy, an online and IRL women's climbing community, released a survey revealing some of the ways in which gender affects women's experiences in the climbing gym.

Flash Foxy's founder Shelma Jun tells us, "Our study showed that women tend to have more spaces within the gym where they feel uncomfortable. They tend to have a higher rate of being harassed or having microaggressions against them. Just because women are physically able to climb as well as men does not mean that sexism or misogynistic behaviors don't exist."

Shortly after publishing the study, Jun (who has been active in the sport for nearly seven years) wrote an article for Outside summarizing the survey's findings. Almost immediately she found herself at the apex of an online outrage storm. "There were all these forums, like 30-page forum threads, about how wrong I was and how I hate men," she says. "Some said even cruder things like, 'If women don't want to be looked at, they shouldn't come to the climbing gym.'"

The attention she received through that survey and through the work she's done in the community since has established Jun as one of the most well-known advocates for female representation in climbing, but being the face of a cause is something she admits she still struggles with at times. "People can be really mean online," Jun says. "I try to remind myself that if I am trying to create social change — if I'm trying to change the status quo and I'm making everybody happy, I'm probably not doing a very good job."

One of Jun's crowning achievements in the sport is the creation of the Women's Climbing Festival, an annual event she founded back in 2015. In the festival's first year, tickets sold out within 24 hours. In its second year, they sold out in less than a minute with an 800-person waitlist. The community's response to this type of event was resounding. Now in its fourth year, the festival has expanded to include a second location in Chattanooga, Tennessee, to keep up with demand. What Jun initially envisioned as "30 or 40 women in the desert hanging out" has evolved into one of the most anticipated events in women's climbing.

Despite the societal setbacks, Jun seems hopeful about what the future might hold not just for women, but for all kinds of people in the mountains. "You're seeing more women, more people of color, more queer folks, more diverse people in climbing than you're going to see in so many other sports," she says.

That is precisely where Jun's friend Bethany Lebewitz of Brown Girls Climb comes in. Like Flash Foxy, Brown Girls Climb, began as an Instagram account and has since evolved into an online and IRL community focused on empowering self-identifying women of color to feel welcome and supported in the outdoors. Lebewitz now works with a team of women who host meetups across the country.

Lebewitz first realized something like Brown Girls Climb was needed when she moved from Texas to Washington, DC. "I noticed the climbing scene in DC is really diverse," she tells us.

"But when I went outside — at least at the time — it completely dropped off. I typically was the only person of color on the crag."

Lebewitz figured the drop in numbers was most likely related to accessibility. In order to transition from the gym to outdoor climbing, climbers typically need a car, equipment, and someone with the knowledge to guide them. Lebewitz says, "I thought, 'If it's a matter of organizing people… I have a car. I would be happy to take people in DC to go climbing outside. I can do that, but I need to make sure they are interested and that I continue to connect people.'"

Lebewitz's vision began to take shape when she teamed up with Brothers of Climbing (another organization working to make the rock climbing community more diverse) in 2017 to create Color the Crag, an annual four-day festival celebrating climbers of color. "Color the Crag shifted what climbing culture could be and really what it is," Lebewitz says. "The leadership and the participants are all people of color coming from different ethnic backgrounds, and so the culture of the festival — the culture of climbing — shifted in a really dramatic way that was kind of mind-boggling to people."

Overall, Lebewitz measures the success of her work by how supported and encouraged her community feels within the climbing world. "You're only going to want to go on a trail so many times after being stared at, or looked at, or called racist names before you're like, 'You know what? Maybe the outdoors is not for me,'" Lebewitz continues. "The same goes for women. How many times do we want to tolerate sexism in the climbing gym before we leave? But if you know you have a community around you, encouraging you to continue, and actively fight against the system — well, then things might be a lot easier."

THE FINAL FRONTIER

As swiftly as climbing culture is changing, progress slows as altitude rises. No one knows that better than 33-year-old professional ski mountaineer Caroline Gleich. As Gleich's clout in the sport continues to grow, so does her fan base. Currently, Gleich has more than 151K followers on Instagram. But with online notoriety comes the unfortunate influx of criticism that, as for so many women with public platforms, people feel inclined to send Gleich's way.

Four years ago, she began experiencing harassment online from a dozen different accounts, most of which sought to cast doubts on her ski mountaineering abilities based on the fact that she is a woman. While disturbed by the comments, Gleich didn't feel it was "socially acceptable" to talk openly about the bullying at first.

"I just wanted to delete them, block them, sweep it under the rug," she tells us. But after it continued for years, she changed her mind. "I had to find my power in the situation," she says. "I had to step into a position of ownership by talking about it candidly and honestly."

The harassment reached an extreme when she received a voicemail from an unknown number. The man on the other end asked if she could teach him how to be a "silver spooned little b*tch with like, an awesome Instagram feed." While transcribing the voicemail, Gleich came to the realization that the multiple accounts harassing her were all tied to this one person. After she asked her followers for help to identify the bully, her massive social media following led to the man being unmasked.

Gleich's harasser has never admitted to sending the messages or leaving the voicemail, but she was able to find some sense of closure while filming her short documentary Follow Through with REI. "We used his actual voice in his voicemail in the intro to the film," she says. "I felt like that was a really brilliant way for me to hold him accountable, without using his name."

Make no mistake, though: Gleich's success as a professional ski mountaineer is not unfounded. For five years, Gleich worked tirelessly to become the first woman to ski all 90 lines described in Andrew McLean's The Chuting Gallery, a beloved guide to steep skiing in Utah's Wasatch Mountains. It was a deeply personal project for Gleich; her half-brother died in an avalanche while skiing one of the lines in the book. In 2017, she finally completed the task and carved herself a place in mountaineering history. Unfortunately, the euphoria of accomplishing a lifelong dream was cut short when she was accused of hiring guides to help her complete the project.

"It was really frustrating because it was another way to attack my credibility and make me prove it again," she recalls. "That's one of the most common things you see when you're not the majority group in an activity or in a space. You just constantly have to prove over and over that you're capable of being in that place. Whether it's a workplace, an organization, or in mountaineering."

Ultimately, Gleich decided to write an op-ed for Outside to set the record straight. "When you're constantly met with that reluctance or that skepticism about your ability and being capable to be up there, it's hard for it not to erode your self-esteem a little bit," she admits.

In spite of all the adversity she's faced throughout her career, she remains as determined as ever to continue ski mountaineering in a way that feels authentic to her. "I approach the mountains with compassion, empathy, kindness, and patience. I try not to be 'agro' or macho. I try to take some of the ego out of it," she says. "I believe that my different approach and point of view is sort of rooted in my more feminine personality."

Gleich explains: "Being who I am and looking how I do, it's often surprising to people when I say, 'I'm going to go climb that mountain.' There is a part of me that likes to challenge people, and their snap judgments of what a woman is capable of."

Like Kitty Calhoun, Gleich has proven time and time again that she is more than capable of holding her own in the male-dominated world of mountaineering, but she still hopes more women will eventually join her on the slopes. This year, Gleich is headed to ski on Mount Everest to kick off the first project for her foundation Big Mountain Dreams, which focuses on protecting mountain environments and elevating the voices of women in the outdoors.

"When I ski a big line or accomplish a big goal with another woman, it's just such different experience throughout the day," Gleich says. "It's really nice to be in a space where you can be 100 percent who you are — where I feel I can be the absolute best version of who I am."

“A Woman’s Place” is a series spotlighting the women making bold moves in male-dominated industries. See all editions of the series here.

Written by: Cortney Clift

Design by: San Trieu