The burden is heavier than you might think.

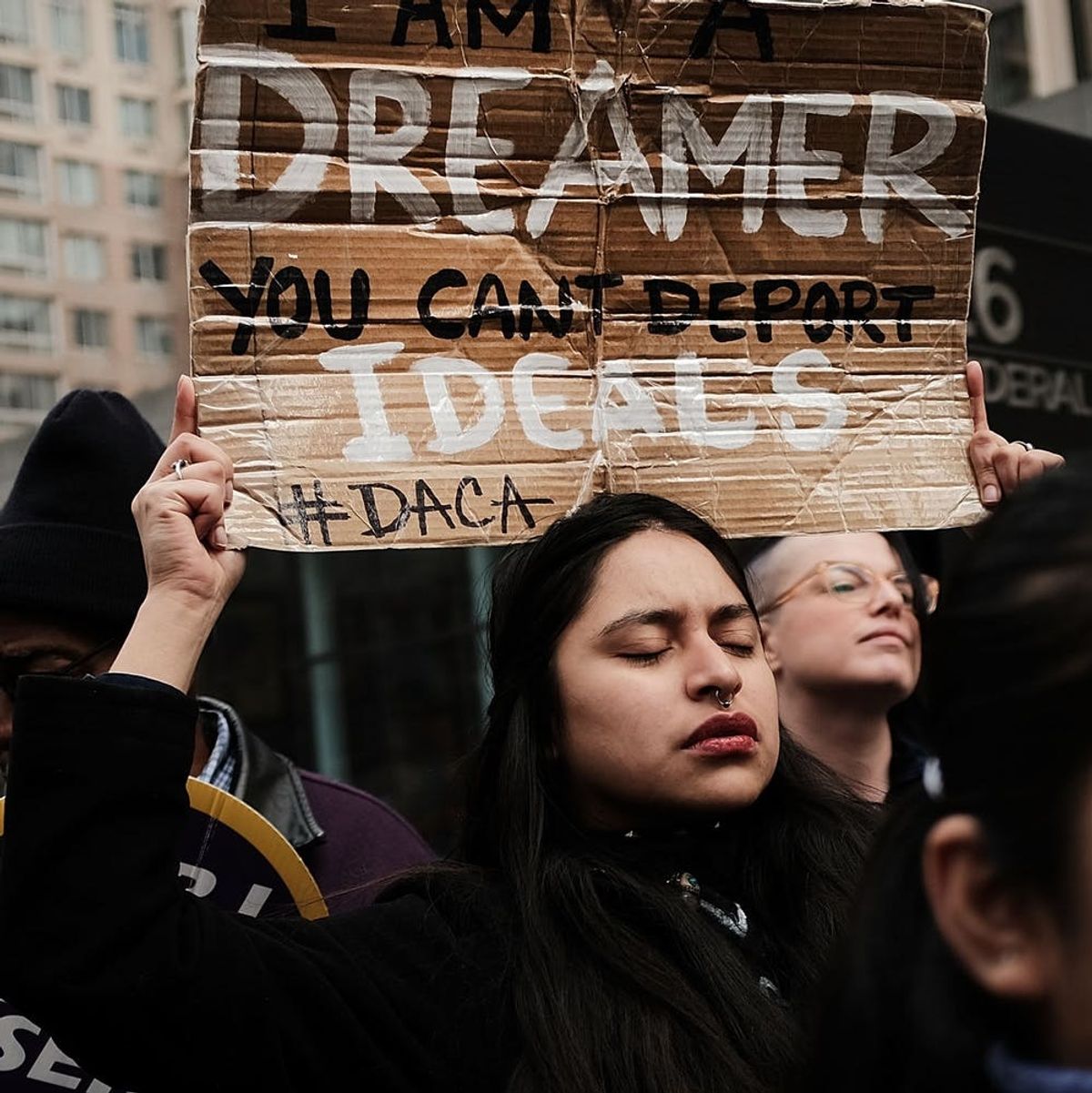

Fear of Deportation Has Heartbreaking Mental Health Repercussions

Last September, President Trump announced his intention to end Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), a federal program protecting nearly 700,000 immigrants known as Dreamers — primarily young, Latinx adults — from deportation. The legislation saga began last week, resulting in a federal government shutdown until the House and Senate could agree on a budget. On Monday afternoon, Senate Democrats reached an agreement, but its many critics argue that the compromise throws DACA recipients under the bus.

Current legislation against Dreamers represents just a sliver of Trump’s anti-immigration rhetoric, but it surfaces a broader reality affecting undocumented immigrants — many of whom left their countries to escape risks of violence and who now find themselves in a landscape that feels equally threatening, in a different way. While they crossed the border hopeful to improve their lives, asylum-seekers live in significant, ongoing state of stress about being deported, which can mean danger for their mental health.

We know for sure that stress about the potential deportation takes a toll on immigrants’ physical health: One study showed that female migrant farmworkers who admitted they felt this ongoing fear had higher cardiovascular risk factors. The most fearful women in the group had higher levels of body fat, wider waists, and were more likely to be obese, all of which contribute to health risks.

Dr. Ernesto Castaneda, professor of sociology at American University and author of the forthcoming A Place to Call Home: Immigrant Exclusion and Urban Belonging in New York, Paris, and Barcelona, traces immigrants’ physical health issues back to their emotional stress. When he and his team interviewed 35 undocumented immigrants in El Paso, TX, mental health assessments showed several had untreated depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

In some cases, Castaneda says, stress on immigrants began on the other side of the border. “Many of these people coming in the last decade are escaping a lot of real violence, like extortion and drug wars. Several of the people I interviewed saw people being killed on the streets back home,” he tells Brit + Co.

Even though life in the US might be objectively “safer” than their lives in Mexico and Latin America, undocumented immigrants experience near-constant anxiety about being turned in to immigration authorities and sent back to an environment of imminent danger. (The decision, earlier this month, to overturn over 250,000 Salvadoran immigrants’ TPS status and deport them to one of the most violent places on Earth poses one striking example.)

“Live like this for an extended period of time will affect your sleep, your physical health, your ability to work, and then your finances. It’s a vicious cycle that’s not doing anybody any good,” Castaneda says.

And it’s not just near the border. In a 2016 survey conducted by American University, more than a quarter of Latinx residents in the Washington DC area said that their fear of police affected their lives “a lot,” citing specifically the fear of deportation. This type of fear is all-encompassing, both ravaging the bodies of those who live with it and preventing them from seeking treatment due to a language barrier, lack of insurance, and/or fear that medical professionals will alert immigration of their status.

Built-in isolation compounds the already complex issue. While social interaction is clinically recognized as a preventative factor for mental health, Castaneda says undocumented immigrants are often afraid of making new friends that won’t understand their status or, worse, will notify authorities. For the same reason, immigrants are less likely to take advantage of resources at local non-profits, attend church, or take part in community events. Day after day, Castaneda says, most of them just go to work and come home, but the fear follows them even there.

It’s common for employers and landlords to abuse power by blackmailing immigrants via wage theft or refusing to address repairs or unsanitary living conditions. As such, many immigrants live and work in environments that are potentially hazardous for both their physical and mental health.

Stigmas around immigrants — the widespread, hateful assumption that undocumented Latinxs came to America to ride the welfare system without contributing to the economy — likely increase the risks they face. In reality, many didn’t have a choice but to escape their country, and the vast majority work, contribute to the economy, and send their kids to school just like the rest of us.

Castaneda says many Mexican immigrants he interviewed were actually successful business owners back home who had never planned to come to the US in the first place — until they were extorted or otherwise threatened, at which point they crossed the border, stayed with visas, and then remained in the states undocumented. If they go back to Mexico, they could be killed. But if they stay here, they don’t have a choice but to keep quiet about all that ails them. While their silence destroys their mental health, speaking up could literally cost them their lives.

“These people are constantly looking behind their shoulders. One woman told me she looks out the window every afternoon until her husband pulls in the driveway,” Castaneda says. “When he comes back from work, she feels like she can breathe again. She made it another day.”

What are your thoughts on the mental health burden facing immigrants? Tell us your thoughts @BritandCo.

(Photos via Spencer Platt/Getty)