As more traditional Peruvian art forms get a second chance to shine, it’s the country’s women who are aiming the lights.

Peru’s Tourist Boom Is Creating a Renaissance for Female Artists

On a mountain, 12,000 feet above sea level, an ancient Inca trail leads to the small village of Choquecancha, Peru. There, around a sharp switchback, my group and I find Señora Maria Valentina Quispe waiting under an old stone archway framed with fresh flowers. The scene is so picturesque that it could be mistaken for an altitude-induced hallucination.

Quispe smiles widely as we approach. She’s dressed in layers of traditional Peruvian weavings with a basket of rainbow-colored flower petals in her hand. Atop her head sits a felted bowl-shaped hat filled with a delicately arranged bouquet nesting inside – a symbol representing both her high status in the community and the fact that this day marks a special occasion. One by one, we walk down to greet Quispe, who welcomes each of us with a sprinkle of the flower petals over our heads, followed by a kiss on the cheek.

Crossing into Quispe’s garden, we are transported to another world entirely. Flowers of every color cover the hillside while a row of other female weavers sit along a stone wall – all of them dressed in ornate, handmade weavings like Quispe’s. Some spin spools of wool and chat quietly amongst themselves. The tour guide introduces them all by name: Mercedes, Carmen Rosa, Margarita, Maritza, Marina, Isabelle, and a dozen others.

These 20 women are part of Wiñay Warmi (“women who grow” in Quechua), a group of women working diligently in their remote village to preserve and revitalize an ancient style of weaving. Through a translator, Quispe announces, “This is my team of weavers. We are artisans. We were losing this skill until all of you visitors helped to bring it back.”

Until recently, a tourist visit to Choquecancha was a rare occurrence. The community is perched on a relatively isolated edge of the Amazon jungle. With limited access to a nearby market or Peru’s growing tourism industry, the community’s time-intensive artform was dying.

Enter: Mountain Lodges of Peru (MLP), a luxury tour company that formed a relationship with the people of Choquecancha and the village’s weavers in 2015. After talks with the residents and consultation with a social anthropologist, the tour company began bringing small groups to town to visit the women’s workshop and buy their goods.

While tourism booms can be problematic for small communities like Choquecancha who don’t always reap the economic benefits of foreign travel companies’ local dealings, when handled delicately, tourism can act as a lifeline. So far, that’s been the case for Wiñay Warmi. Since the guided visits began, the women have been able to build an exhibition and retail space for their weavings. They now have plans to open a local weaving school, and with assistance from MLP, Quispe traveled to another community, Viacha, to lead a series of weaving workshops for the people there.

It’s not just Choquecancha where Peru’s tourism growth is giving old art new life. In Cusco, local artist Berenice Diaz has found a way to connect the booming market with her mission to preserve culturally historic art techniques.

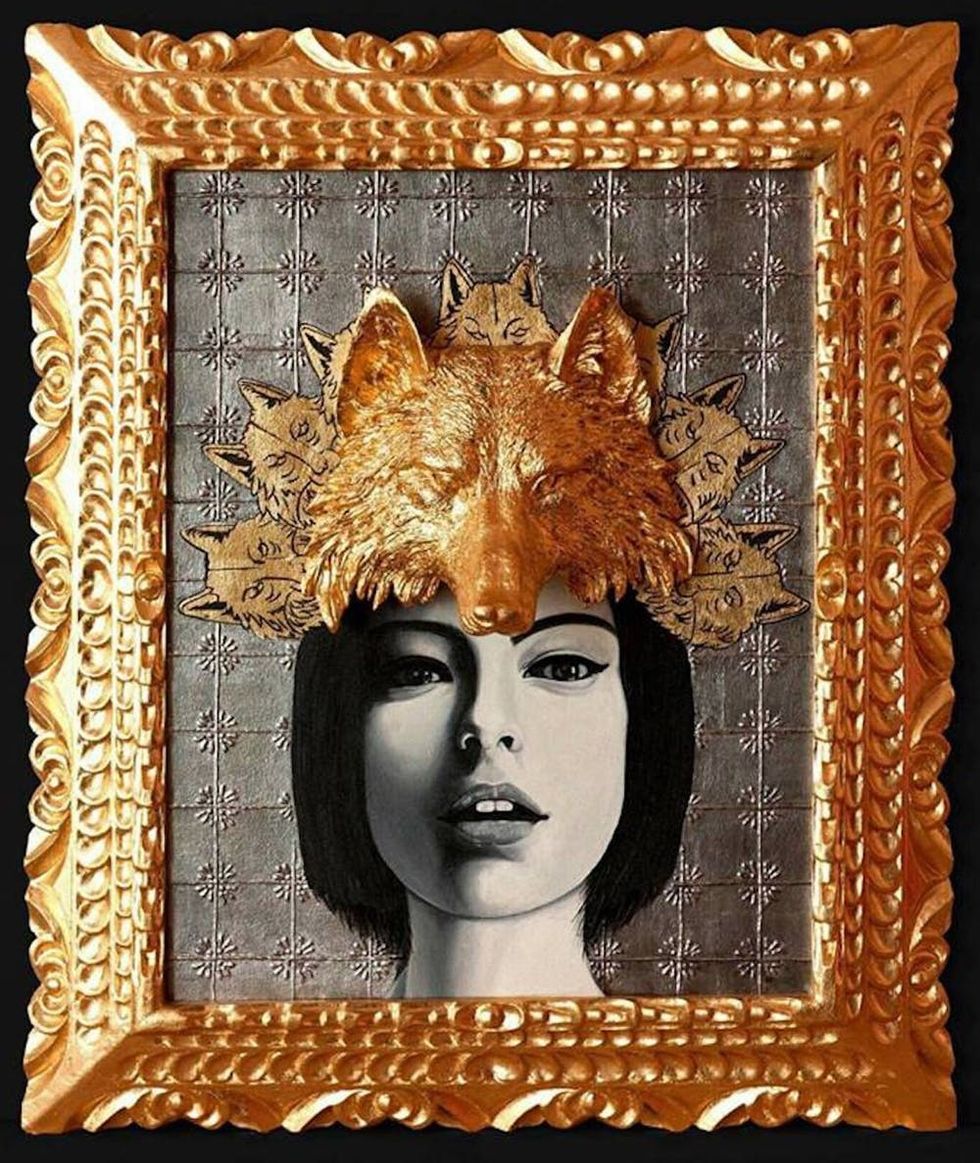

Diaz is the founder of the women’s artist collective Totemiq, a group focused on revitalizing and preserving ancient Peruvian artforms through collaborations with modern-day artists. Diaz also hosts an “Art Trail” tour, which takes tourists into the workshops of local artists in Cusco.

To the Cusco visitor, it may seem like the art scene doesn’t need much support. Around every corner is a shop filled with woven blankets, embroidered pillows, and alpaca sweaters. But Diaz is quick to clarify: “The mainstream [art] is not considered art. It’s considered handicraft. It gets reduced to souvenirs and it’s not valued at as much as it should be. I want to transform [these crafts] into something really valuable.”

Over coffee at the idyllic El Retablo hotel, Diaz talks about a recent project she produced that involved covering a series of ceramic bulls (a common Peruvian symbol of prosperity and protection) in a combination of gold leaf — a technique popular during Peru’s colonial era — and female-centric paintings. She recruited a master colonial ceramicist to work on creating the bulls and a group of young women from the local art school to help execute the rest of the installation.

While Diaz has managed to make a life for herself as an artist in the area, she admits that the country’s societal norms can still be challenging for female artists.

“The society here is very traditional – very machista. It’s about men, men, men. When I started developing new ideas I found it was only men producing,” she says. “When I left school it was so hard to start making art for a living. So I decided to put together this women’s artist collective so that I could incorporate the new generation more easily into the art world. They’re producing art with a base in tradition.”

Now, as more traditional Peruvian art forms get a second chance to shine, it’s the women who are aiming the lights. Given Peru’s increasingly popular status as a bucket list destination, Diaz has high hopes for the future of female creatives in her country.

“I’m dreaming about opening up a new art school and bringing back the art culture [here] to what it once was,” she says. “I want to create a new industry. I want to educate a new generation to do something powerful.”

(Photos by Cortney Clift and courtesy of Totemiq)