Why wait any longer for the trip of a lifetime?

The Pride of Africa: Why Now Is The Time to “Come Home” to Kenya

I’ve wanted to visit Kenya my entire life. And yes, there are other nations just as known for their wildlife or their endless plains. Yet, for reasons I can’t quite identify, I knew Kenya was the one place I needed to visit before I died. It was my ultimate bucket list adventure — one I (wrongfully) assumed required a honeymoon to experience. But unlike so many of the things in life that we imbue with hope and expectation — that first kiss, first job, first anything — the reality of my trip to Kenya exceeded my wildest dreams. And I knew it would from the moment I landed in Nairobi and the Deputy President shook my hand. “Welcome home,” he said.

(Maasai Mara)

It was the last Monday of October when I arrived in Kenya, a passenger on the first nonstop flight from New York City. The cabin erupted in applause when the Kenya Airways aircraft touched down in Nairobi. It was a historic moment, especially fitting from an airline known as “The Pride of Africa.”

There had been a celebration at the departures gate at JFK, with balloons, streamers, and an air of eager anticipation swirling around the Kenyan and American passengers. I boarded the aircraft behind an intimidating crowd of journalists and reporters, chief executives, and “influencers,”

Onboard, I’d been too excited to sleep. I spent the majority of the maiden voyage drinking Baileys, an activity which culminated in midnight Swahili lessons from the patient, amused airline staff. (Thank you, Peggy, or should I say: Asante).

(Inaugural Flight Kenya Airways)

My sleep-deprived (and semi-intoxicated) condition rendered the sight of the drummers and dancers greeting us on the tarmac at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport 15 hours later even more surreal. Kenyan politicians welcomed us with speeches commemorating the inaugural flight’s significance, not just for trade and tourism between Kenya and the US, but as a symbol of connectivity between Africa and the rest of the world.

Deputy President William Ruto spoke of Elizabeth II becoming Queen while in Kenya (as fans of The Crown well know) and of Barack Obama being the son of a Kenyan man, before concluding: “It doesn’t matter where you come from.”

“Whether you come from Asia, whether you come from Europe, whether you come from Australia, whether you come from wherever: Kenya is the capital of mankind. This is the place where humanity began. When you come to Kenya, you are coming home.”

(Fairmont the Norfolk)

Nairobi

I planned on spending a few days in the Kenyan capital before venturing northwest to Nanyuki, in the foothills of Mount Kenya. Then I would finish my trip by heading southeast to the tented luxury of the Maasai Mara, a game reserve in the Great Rift Valley so emblematic of Kenyan history and culture that its name was painted upon the Boeing 787-8 Dreamliner I flew in on.

My well-planned itinerary was quickly thwarted, however, when the drive from the airport took longer than expected — hours longer. But “precise,” I quickly learned, was beside the point in Kenya, a land where mornings become afternoons and afternoons stretch into evenings without much restriction or fanfare.

I was introduced to the concept of “Kenyan time” that first day when I watched my taxi driver turn off the engine at a red light. Punctuality was not only unexpected but discouraged. Three hours late to the party? Come as you are, when you feel like it. Now, this was a wavelength I could get in on. Finally, I thought, a place where I felt fully understood.

(Ol Pejeta Conservancy)

When we arrived at our destination, the iconic Fairmont The Norfolk hotel, it did not disappoint. The hotel’s pastel architecture and tropical gardens resemble a glamorous, turn-of-the-century fever dream — and it is. An urban oasis in the heart of Nairobi, the private courtyard has long provided a lush hideaway for infamous lushes (one of the hotel’s famed regulars was none other than Ernest Hemingway), the staff serving Sundowner cocktails each evening until far past sunrise.

Another manicured destination for literary lovers is found only 20 miles from downtown Nairobi at the formal gardens and restaurant of the Karen Blixen Coffee Garden, where the Out of Africa author’s original farmhouse once stood. (The Karen Blixen Museum is half a mile down the road).

I made the journey to utter the iconic opening words of Blixen’s memoir, in the spot where she once stood: “I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills.”

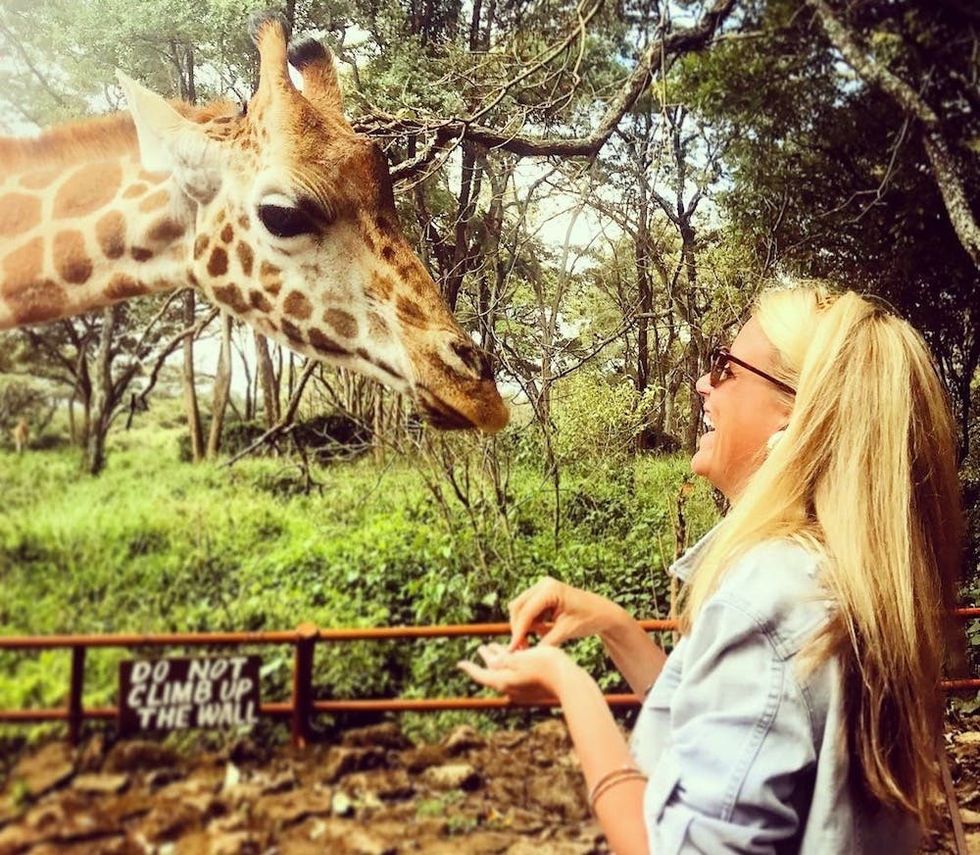

You also don’t need to leave Nairobi to see (and help protect) Kenyan wildlife. I saw my first glimpse of the country’s passionate conservation efforts when I visited the Giraffe Centre and The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, where I adopted an elephant named Kaisa.

(Giraffe Centre)

At the Giraffe Centre, I purchased a child’s drawing of two birds. The sale of each drawing provides a bus ticket for one underprivileged child from Nairobi to visit the center to see a giraffe for the first time. I felt immense satisfaction knowing my tourist dollars supported wildlife preservation and helped to provide the funds for these efforts to continue.

“The problem is never with the wildlife, it’s the human beings that make this challenge,” Stanley Kosgey of the Giraffe Centre shared with me. Nevertheless, he remained hopeful: “If you want to make a better tomorrow, it’s about changing the mindset of the next generation. Suggestions from little kids are always brilliant; it shows they want to save the world.”

(Maasai Mara)

Many travelers skip Nairobi in favor of seeing more big animals. But there’s more to Kenya than just game drives. To catch a connecting flight immediately upon landing in the Kenyan airport is to miss the other exchanges that occur while traveling, person to person, not person to elephant.

The second night, I attended an event at the Kenyan International Convention Centre and spent the evening watching the sunset with an events department intern, John Mutai, who was roughly my age. He, too, loved to write. He read his articles to me and I gave feedback, while he critiqued my Swahili. Obviously, we took a selfie. When I checked my phone later that night, I saw he’d shared our photo it to Instagram.

“Born in different cultures but united by the same passion,” he wrote.

(Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Photo via Kate McCulley)

Mount Kenya

I was staying at the Mount Kenya Safari Club, a luxurious resort originally founded as a hunting club by A-List Hollywood glitterati in the 1960s and frequented by the likes of (who else?) Hemingway. The hallowed walls are adorned with taxidermy, representing an extravagant fantasy of Hemingway’s big game memoir, Green Hills of Africa.

Today, the club exists as a conservancy — and it is a remarkable one at that, despite its misleading interiors. The Mount Kenya Wildlife Conservancy is working to save the Mountain Bongo from extinction under the watchful eye of Donald Bunge, a man who managed to turn one chicken at age eight into a herd of sheep by age 10, and a dozen cows by high school.

As if that weren’t a strong enough omen on its own, there’s no more auspicious a place to begin such a resurrection than beneath the shadows of Mount Kenya, where the nearby Ol Pejeta Conservancy is literally overflowing with animals.

(Mount Kenya Safari Club)

The second-highest peak in Africa after Mount Kilimanjaro, Mount Kenya was considered to be a holy place by the area’s indigenous tribes. Kenya means “God’s resting place” in the three native languages spoken in the area, and is believed to be the source of the country’s name. The Gikuyu and Embu believed God lived in the mountain, while the Masai believed it was the home of their ancestors. The doors in the village were built to face the mountain.

Mount Kenya is now a World Heritage Site, and the ancient volcano last erupted millions of years ago, but its power is felt to this day. When I visited Nanyuki I couldn’t argue with their logic — there was something spiritual about the place, something otherworldly.

(Bush breakfast at the Mount Kenya Safari Club)

A group of elephants, aptly, is called a memory. And one particular memory I’ll never forget was while I was horseback riding to breakfast one morning. (Another heavenly element of safari life? The bush breakfasts and Sundowners.) Mount Kenya was barely visible in the misty morning fog.

When I heard a low roar from the rainforest ahead, I looked up to see bushes shaking with the grunts and trumpets of a large animal, hidden behind the trees. When a pair of elephants emerged from between the brush, I was so in awe, it literally took my breath away. (Not to mention my iPhone — which says something, considering the triple-digit likes safari Instagrams garner.)

I was transfixed in place. Though the elephants were so close to me, I felt calm and still. Not panicked, but transported, the Talking Heads lyrics come to life: Feet on the ground, head in the sky. It’s okay, I know nothing’s wrong. Hakuna Matata.

It made sense to me that God would want to vacation here, that he would leave heaven for this place instead.

(Members of the Maasai Tribe)

Maasai Mara

The Maasai Mara is magic. You feel it the moment you step onto the plains. There’s something about the air, and even the sky. Flying aboard the Safarilink prop plane to the Maasai Mara, we passed through towering clouds floating like sandcastles above the African bush. The sun streaming through these clouds casts beams of light across the plains. Green and lush in the summertime, the Mara turns a burnt gold in the fall.

When I visited in October, it looked like heaven brought down to earth. Similar to the eternal turquoise of the Caribbean Sea in stormy weather, the savannah retains its golden luster even if the sky is gray. I suppose I always assumed it would be the safari that spoke to me the most, and its charms cannot be overstated.

(Fairmont Mara Safari Club)

In the words of Out of Africa: “There is something about safari life that makes you forget all your sorrows and feel as if you had drunk half a bottle of champagne — bubbling over with heartfelt gratitude for being alive.”

For me, this manifested in tears of joy, particularly when I spotted “the common zebra,” in the words of the witty (and wise) Kepha Ongere, my guide at Fairmont Mara Safari Club. Yet I maintain there is no sight more moving in all the savannahs of Kenya (or grasslands of East Africa, for that matter) than a dazzle of zebra running across the golden plains. Yes, a group of zebra are known as a dazzle, and dazzle they do when flash across the yellow grass of the Masai Mara in early November.

Home is where I want to be, but I guess I’m already there.

(The author with Kepha Ongere)

Though Kenya is legendary for its natural beauty, I found I was most moved by the nation’s rich culture and the people I encountered on my journey. I was overwhelmed by the kindness and hospitality I received throughout my stay, and I was delighted to discover that the place I’d longed to visit was eager to receive me as well.

It was then that I realized all you have to do to make friends is to be three things: curious, kind, and vulnerable. It seems so easy, but for so many people, it’s too difficult. Radical sincerity. Radical self-deprecation.

Safari means “journey” in Swahili, and my travels throughout Kenya felt like a retracing of my own long-forgotten steps, each moment a revelation. By fulfilling my greatest dreams of escape, I was on a homecoming back to myself.

(Maasai Mara)

When I later marveled to my cousin Jason McLachlan, about the weather in Kenya — never too hot, never too cold, almost like heaven — he said, of course, it was perfect.

But the need to protect those spaces is real. The East African grasslands socialized us, forcing us to work together and coexist (like the warthog and the zebra I spotted napping beneath an acacia tree), resulting, quite literally, in growing our brains, expanding our ego, our intellect: The very things that make us human.

Kenya is where we first became human. Maybe it’s where we need to return to feel human again.

Have you been to Kenya? Tag us in your vacation destinations on Instagram.

(Photos via @katherineparkermagyar)