The latest developments in the movement are a major victory for women.

#MeToo Is Taking on Once-Respected Men — and it’s a Game-Changer

Thanks to the #MeToo movement, inspired by a wave of abuse allegations against Harvey Weinstein last year, the systemic exploitation and sexual abuse of (mostly) women by powerful men has become more visible than ever. And while the issue is far from resolved, one thing has become increasingly clear: “talented” men and male artists can no longer fall back on their perceived talent to excuse sexual abuse and misogynistic behavior. And this accountability, in turn, is contributing to an environment in which growing numbers of women and victims of abuse can feel comfortable coming forward, and trust that their voices will yield meaningful change.

Just earlier this month, a slew of brave women spoke up about their experiences with sexual abusers in the literary world, yielding a highly necessary shake-up. Two weeks ago, the Swedish Academy announced that it will not name the Nobel Prize in Literature this year due to a sexual harassment scandal surrounding one of the men who oversee the choosing committee. Jean-Claude Arnault, a French photographer, has been accused of harassment and assault by 18 women; the Academy had been notified in 1996, but it seems that it wasn’t until the advent of #MeToo that accusations began to be taken seriously.

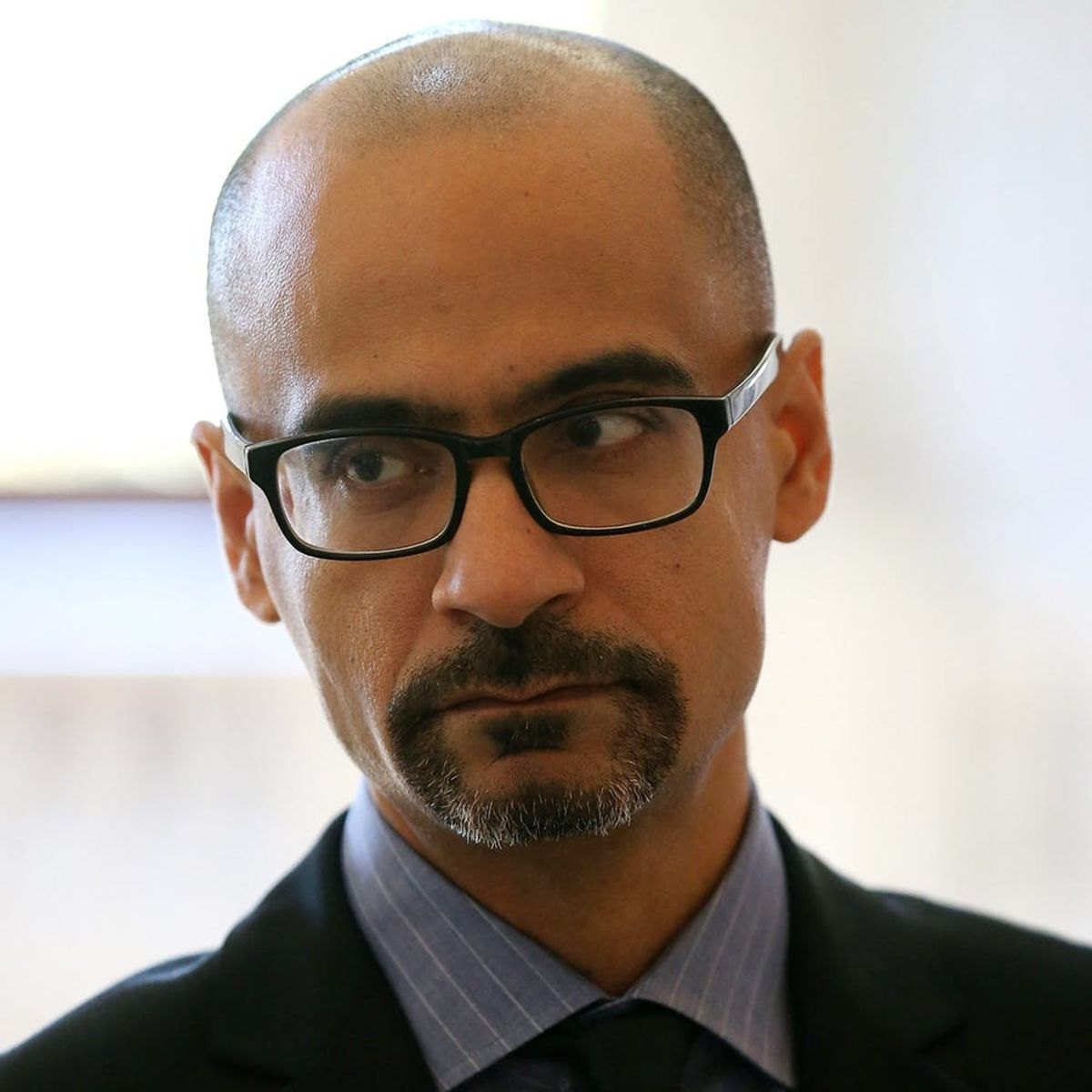

The Swedish Academy isn’t the only major arm of the literary world that’s moving to hold alleged abusers accountable. Last week, the Pulitzer Prize board announced an investigation into the conduct of Pulitzer award-winning author Junot Diaz in light of accusations of sexual misconduct and misogynistic attacks from him, primarily by women of color. MIT, where Diaz is a writing professor, also announced last week that it is investigating him.

#MeToo has been key to publicly exposing the experiences with sexual abuse that women and girls across every walk of life have always been forced to accept as an everyday part of life. One in five women experience rape at some point in their lives, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center; 81 percent of women in the workforce have experienced some form of sexual abuse, and low-wage female workers are disproportionately affected.

And, of course, these numbers must be taken with a grain of salt, considering how a majority of cases of sexual abuse are not reported to law enforcement or authorities. Even among the few that are reported, crimes related to sexual abuse yield the least arrests and convictions, if that offers any insight into how seriously sexual misconduct is taken.

Prior to #MeToo and the pronounced shift toward taking women and survivors seriously, society has long been a hostile space toward survivors. Many who have experienced assault report unease and fear of law-enforcement, victim-blaming questioning, and being forced to relive their trauma. And in terms of sexual harassment and abuse in the professional world, male perpetrators who hold significant clout already exclude and marginalize women who don’t speak out about sexual abuse. The threat of retaliation and loss of opportunity has always silenced women in male-dominated spaces; regardless of whatever talent or artistic genius male abusers at the top of their fields may bring to the table, the shift toward accountability is critical.

Of course, this shift hasn’t come without dramatic pushback. The defenses that only talent and merit should be factored into how we treat men in their professional capacities, and that murky “private life” details shouldn’t deny men opportunities, are prevalent among sympathizers of disgraced male figures. And it’s especially popular with male sympathizers. Consider an essay published in Spiked called “#MeToo is a menace to private life” (written by a male writer) or another essay in the New York Post called “A male backlash against #MeToo is brewing” (shockingly, also written by a male writer.)

But as the alleged abuse by Weinstein revealed from day one, work life can’t be separated from non-consensual “private acts” that serve to exclude and deny opportunities to unsaid numbers of vulnerable women, and help maintain a male-dominated monopoly on industries.

Continuing to give opportunities and platforms to men facing allegations of sexual abuse affirms that people in positions of power can do anything without consequence. The “merit argument” all but suggests men deemed talented — of course, within a society that prioritizes male-centric audiences and male perceptions of talent — have a free pass to behave in any way they want, deny opportunity to however many women they choose, and ultimately reduces women in their fields to collateral damage. It’s a narrow-minded argument that ignores how, as exhibited by the work of Junot Diaz and others, personal misogyny tends to infect artists’ work, just as it ignores the countless diverse artists whose talent and creativity are excluded every day without any sympathy.

Too many are suddenly concerned with the issue of exclusion in art only when it pertains to the removal of men who abuse their power to hurt and deny opportunity to women. But anyone who really cares about inclusivity and ensuring that talented people have a platform would question the current landscape of abysmal representation of female artists and artists of color. Often lacking the connections requisite to success in their industries — connections their white, male counterparts are far more likely to have — there is a very real issue of exclusion in nearly every field. Focusing on male abusers who are faced with consequences for their actions only exacerbates this issue.

There are no more excuses for exploiting and abusing women, nor should there ever have been. Years of protecting and enabling abusive men have silenced and forced women to not only internalize their shame, but also rework their professional lives around the untouchability of abusive male figures. From the Swedish Academy’s decision to not name a Nobel award winner this year, to the Pulitzer Prize board’s investigation of Junot Diaz, our culture of coddling toxic men is slowly coming undone — and this could change everything for women.

(Photos by Mark Wilson + iStock/Getty)