I learned from my immigrant family that citizenship is a privilege and a responsibility.

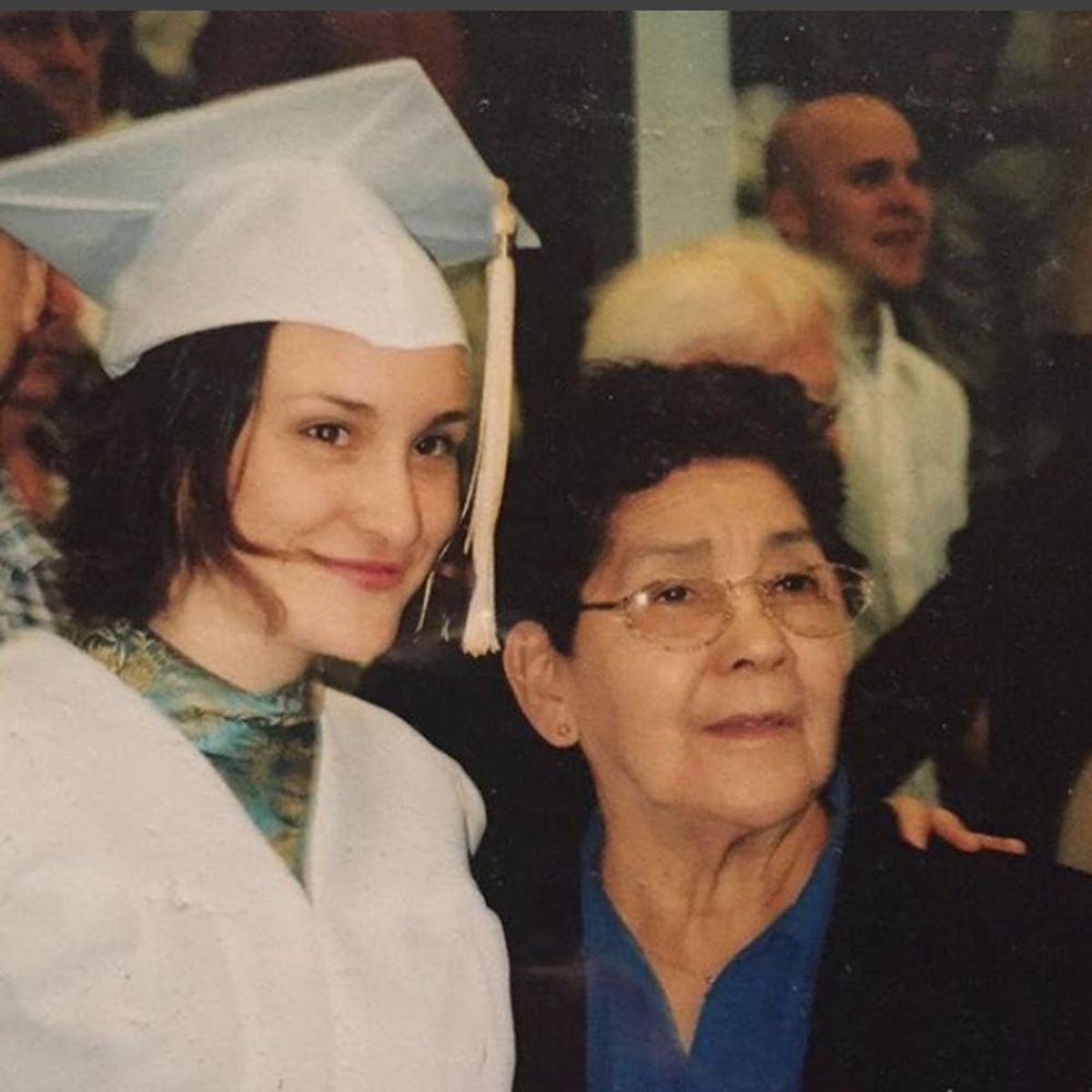

My Mother and Grandmother are Central American Migrants. They Taught Me How to Be a Real American

Brit + Co staffers’ stories on immigrant heritage and the lessons of an American dream.

*

When I was in the third grade, my mom pulled my two younger brothers and me out of school to drive to the state capitol, two hours away, so we could watch my grandmother’s induction ceremony to become a US citizen.

My father had helped my grandmother, who I call Mama Manda, phonetically memorize all the potential questions and answers for her immigration oral exam because she had never learned English — not because she’s lazy or a freeloader, but because she had never been allowed to attend school growing up, and it’s really hard to learn a second language without first-language literacy. But she was smart, so smart. She was smart enough to memorize every single answer to every single question she might be asked, just by sound, and determined enough to want to.

Mama Manda was 65 years old when she became a US citizen and had fled the civil war in El Salvador less than eight years prior. The week after she and my grandfather arrived in our Wisconsin home came the Fourth of July; without even thinking about it, my senior citizen grandparents had dropped to their bellies at the sound of the fireworks’ booms, a reflex from living under a near-decade of bombings and machine gun raids. So, even though her green card status protected her from deportation, Mama Manda recognized the fragility of her good fortune. She wanted the civic responsibility of a vote.

My mom became a naturalized citizen of the United States the year before I was born. She has voted in every local, state, and federal election ever since. My mom recognizes her citizenship as both a privilege and a duty: It is the duty of a citizen to pay attention to the needs of her fellow citizen by keeping informed, and to exercise her vote to ensure that those needs are being met by the political candidate who is best suited to do the job. Mama Manda is now approaching 90 with advanced dementia, but as long as she was able, she held her end of the bargain too. She diligently watched Spanish-language news broadcasts and formed her own positions on the political issues of her adopted homeland — not that Mama Manda ever had trouble being opinionated, I should add.

My dad’s side of the family immigrated from central and eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which wasn’t very long ago either. But I internalized the power of citizenship — and the civic duty that comes with that power — from my mother and her immediate family, who have all immigrated to the US during my lifetime. They were the ones who taught me that we cannot claim to be proud Americans if we don’t pay attention to the broad portrait of what “being American” means, and especially not if we don’t keep ourselves informed about the issues that affect our fellow brothers and sisters.

In some households — even within my extended family, on the side that has enough distance from immigration to take its own citizenship for granted — politics are considered divisive or rude subjects of conversation. But I learned from my immigrant mother and grandmother that “politics” is just a loaded word for the issues that affect us and the people in our communities. To avoid thinking about politics, to skirt the responsibility of keeping informed and making decisions for the greater good, isn’t just a waste of opportunity. It’s spoiled. It’s the behavior of a person who doesn’t value the gift of being an American. And I’m grateful to be the daughter of an immigrant because I can appreciate my good fortune for what it is: fortune.

Citizenship is a privilege and a tremendous power. As I watch migrant children from my mother’s homeland being separated from their parents, as they escape a violence so desperate that my one remaining cousin in El Salvador requires armed guards to protect her family’s home at all times, I am reminded of the power of my vote and my voice. I’m reminded of my fortune — and, I should emphasize, the responsibility that comes with it. And I thank my brown-skinned, Spanish-speaking, civically-engaged immigrant matriarchs for passing those values along. Mama Manda and my mother are the models for what an American should be.

Kelli Korducki is the Senior News Editor at Brit + Co.

(Banner illustration by Yising Chou)