How “MMMBop” Changed My Life

I first heard Hanson’s “MMMBop” in August 1997 at a barbecue in the small town in Maine where my family spent our summers. I was almost 12, about to start sixth grade, and up until that point, my primary exposure to popular music had been my parents’ vinyl collection of Beatles and Paul Simon records. I was naturally introverted, but when one of the other preteens put that song on the boombox and got us all dancing, something in me opened up.

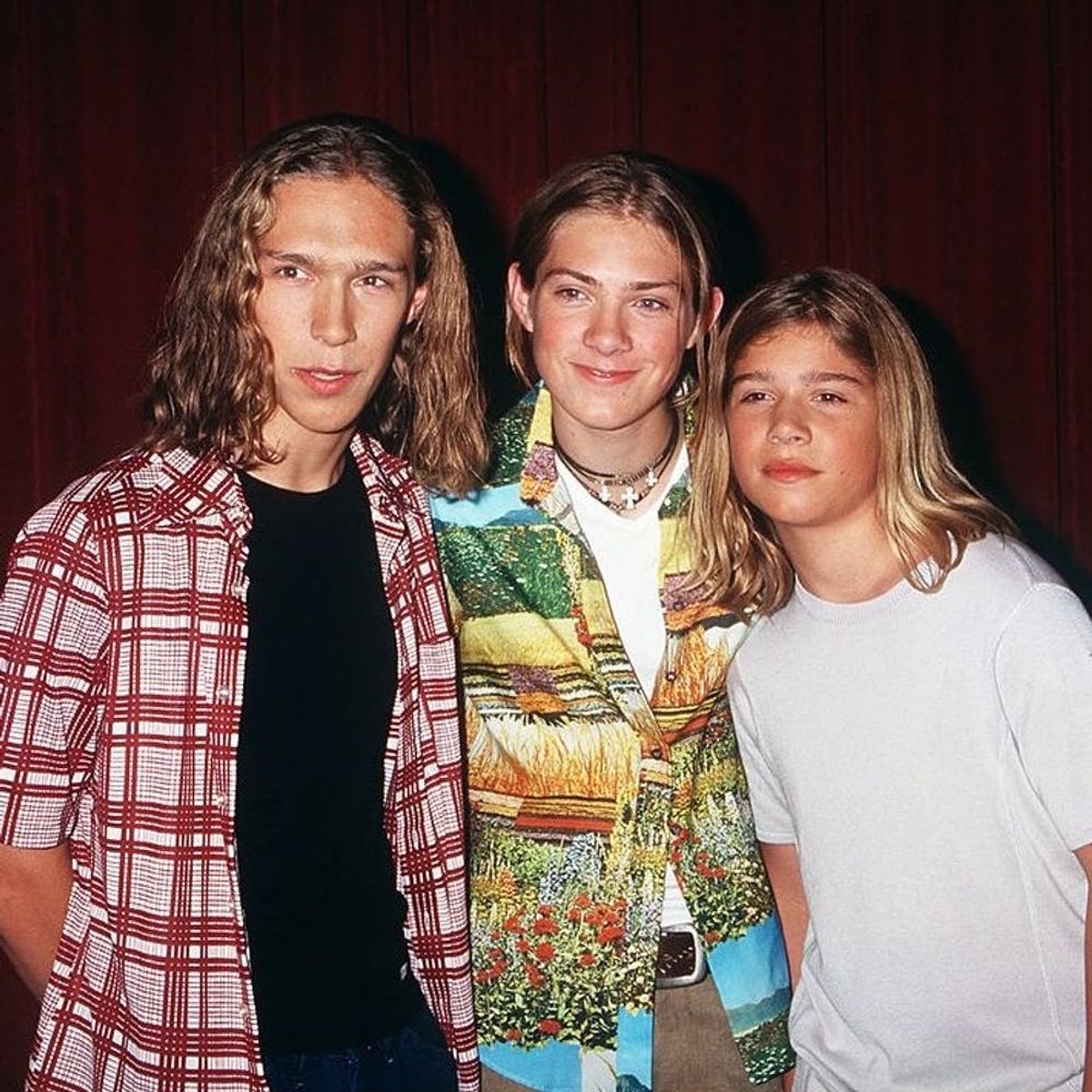

As I would later learn, it wasn’t a coincidence that I loved “MMMBop” immediately: Like me, the three brothers who made up Hanson had also been reared on a steady diet of ’60s rock and roll. (Take a close listen to any of their albums and you’ll hear the influence of Motown and the British Invasion in everything from their harmonies to their bluesy guitar-piano work.) Within weeks I’d acquired my own copy of their album Middle of Nowhere and devoured countless articles about the band, fascinated by the fact that they were my age and wrote all their own music and played their own instruments. Of course, I was also instantly crushing on Taylor.

Although Hanson topped the charts that year, they were not considered “cool” in my sixth-grade class, adding to my perfect storm of misfit attributes. I grew up in a wealthy suburb outside of Boston, where my family’s modest means were the conspicuous exception to McMansions with marble driveways. Even if my parents had been able to afford Abercrombie & Fitch, I was literally too tall to wear most of their clothes; I was six feet by the time I was 13. I had also just been diagnosed with attention deficit disorder (ADHD) and, thanks to the inevitable social missteps that came with not paying close enough attention, way more comfortable living in my own imagination than in the world of other sixth-graders. The mother of one of my classmates, without realizing I could hear her, once described me as “a goose in a flock of ducks.”

Hanson’s song “Weird” provided an even more cogent description of my middle school self: “When you live in a cookie-cutter world where being different is a sin, you don’t stand out but you don’t fit in.” Coming home from school and listening to Middle of Nowhere while I read books for my English and social studies classes was the highlight of my day. Otherwise, I was miserable.

Enter the internet, literally. I’m talking late ‘90s dial-up, Angelfire, alt.net boards, and, yes, Hanson’s website.

Few people know that Hanson was one of the first bands to deliberately cultivate an online fan community. Hansonline.com, their original site, featured a robust message board where the band regularly chatted with fans.

When my family finally got halfway-decent internet in 1998, my AskJeeves search for “where are the other Hanson fans” led me straight to the Hanson message board community. Obviously, the topic threads on the message boards were mostly about Hanson, but some threads branched into more intense conversations about politics and mental health; it turned out I was not the only “Fanson” with ADHD, and for the first time I felt safe talking to other people about their experiences with the disorder. In fact, behind the safety of that screen, I started to discover that I was not nearly as weird as I thought.

At school, being different from the other kids was what defined me. I constantly tried to make myself as small as possible to avoid whispers, sneers, or pointing and laughing. But online, nobody could see how tall I was, or whether or not I was wearing designer clothes, or whether I was looking off into space in a moment of distraction. The solace I found in Hanson’s music was a shared norm rather than a scarlet letter. In this space, my defining feature wasn’t being odd; I could actually be a complex, creative person. My minor claim to fame on the message board under my username, HansonSheepY2K (named for my favorite animal), became the short comedic fan-fiction skits I would write imagining the band in various absurd or fantastic situations. I even taught myself HTML to create a Hanson website on Geocities. On the same day a girl in homeroom made fun of my clothes, my Hanson site was approved to join what was considered an elite fan collective of Hanson “webmasters.”

My parents strictly monitored my computer time, so the Hanson message board became my before and after-school hangout. I would get up at 5:30 in the morning to chat for an hour before I had to go to school, and then I’d spend another hour on the board when I got home. It was the equivalent of taking a self-esteem pill before going into the ring and another one to boost myself back up afterward.

Over time, however, I began to bring more and more of my online self to my real life. Through the message board, I coordinated meetups with other local “Fansons” when the band began touring again. I even discovered that a few “closeted” fans attended my school. The fan fiction and HTML skills eventually evolved into creative writing classes and web editor roles on school publications when I got to high school.

By graduation, the Hanson community had become far less central to my life.

Still, the band’s music remained the soundtrack to my life. Their Underneath album mapped my first breakup, while 2010’s Shout It Out served as motivation while completing my graduate thesis in government.

To this day I remain a “Fanson” — in large part because, like me, Hanson also stopped defining themselves by their ability to keep up with the popular crowd. They ditched a major label to launch their own, embraced the music they wanted to make, and used their platform to champion causes they believed in. Come fall, Hanson will mark their 25th anniversary with a world tour. You’ll find me in the audience, singing along.

Meg Massey is a New England nerd who has made Washington, DC her adopted home. When she is not writing or telling stories on stage, she is over-caffeinating herself with a good dark roast, dancing in costume with her competitive karaoke league, or binging British crime dramas on Netflix. You can read more of her work online at megmassey.net.

(Photos via Mark Mainz/Brenda Chase/Getty)