An “all-sides” narrative isn’t at all helpful when one side is based on harmful misinformation.

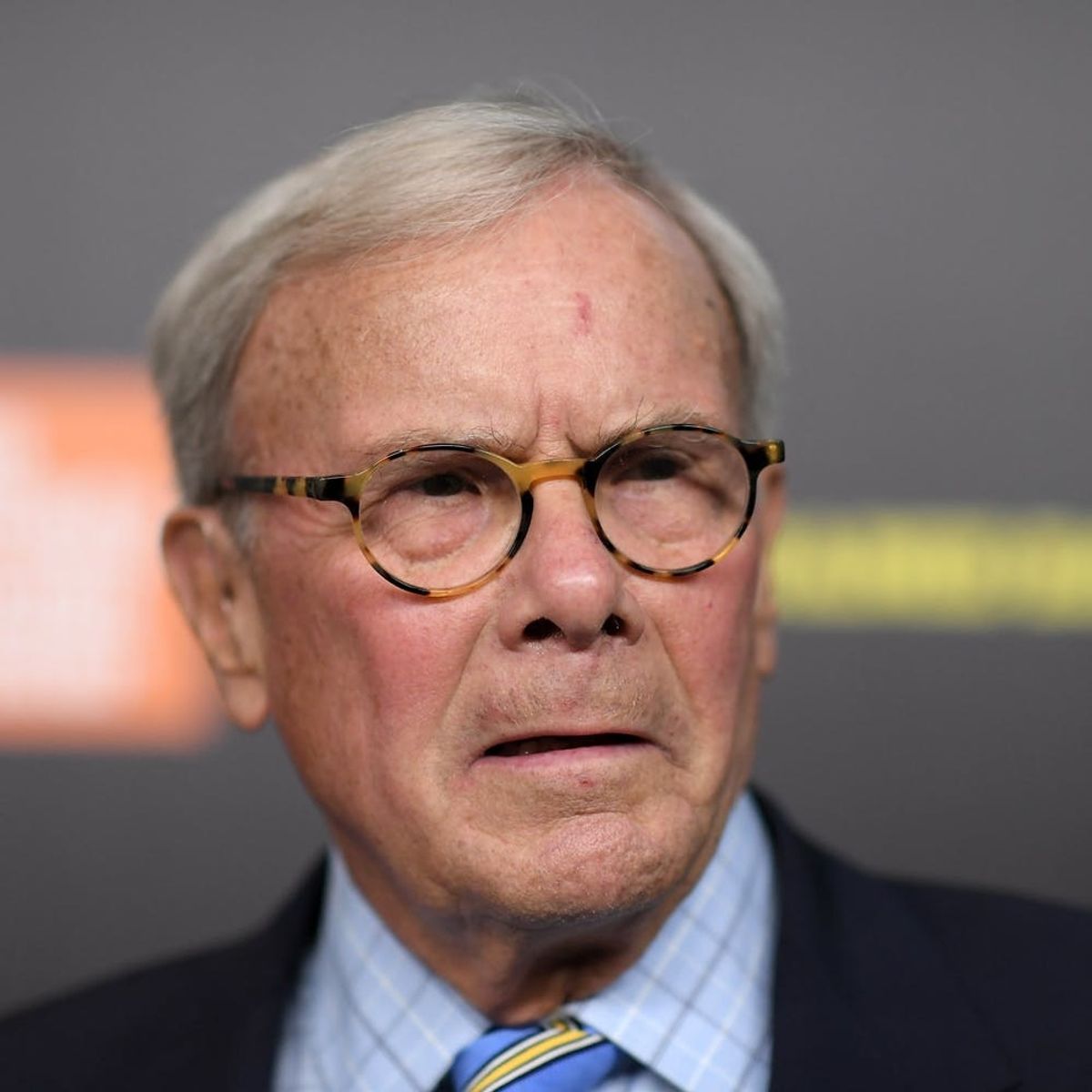

Tom Brokaw’s Comments About Hispanic Americans Show How Insidious Ethnic Stereotyping Is

Veteran journalist Tom Brokaw had to apologize Sunday, January 27, after making disparaging and inaccurate remarks about Hispanic Americans purportedly needing to “work harder at assimilation” into US culture. Brokaw made the statements in question during an appearance on NBC’s Meet The Press, and in so doing, showed a clear lack of understanding of Hispanic-American history and how diversity has helped shape the country.

During a roundtable discussion on immigration reform and border security, Brokaw stated his belief that Republican voters and politicians feel threatened by the political gain of a largely Democrat-voting Hispanic-American contingency. But Brokaw also cited cultural concerns that he believes are at the root of non-Hispanic Americans’ stance on immigration.

“It’s the intermarriage that is going on and the cultures that are conflicting with each other,” he said. “I also happen to believe that the Hispanics should work harder at assimilation. That’s one of the things I’ve been saying for a long time. You know, they ought not to be just codified in their communities but make sure that all their kids are learning to speak English, and that they feel comfortable in the communities. And that’s going to take outreach on both sides, frankly.”

WTH, @tombrokaw? “Hispanics need to work harder at assimilation and making sure their kids learn English”@latinorebels @DefineAmerican @robvato pic.twitter.com/Q1BZnRpWtF

— Andrea Leon Grossmann ☀️ (@AndreaLeon) January 27, 2019

Panel participants, particularly PBS News Hour White House correspondent Yamiche Alcindor, pushed back against the 78-year-old broadcaster. People also expressed their disapproval online.

Congressman Joaquín Castro (and brother of 2020 presidential candidate Julián Castro) responded to Brokaw’s comments by tweeting that it’s “unfortunate to see xenophobia pass for elevated political commentary,” before giving a brief history lesson on how Hispanic culture has been traditionally seen in the US — and what forced assimilation has done to Hispanic communities.

“To give some context as to why this matters,” Castro wrote, “in Texas into the 1950s (and perhaps after) Spanish was literally beaten out of children. At many schools if you spoke Spanish you were hit by a teacher — spanked with a ruler or paddle.” Castro also pointed out that this institutional ostracism often led Hispanic parents to avoid passing down their families’ language and culture to American-born children.

“Yet another irony is the fact that many who prefer getting rid of ‘hyphenated Americanism’ refer even to [second- and third-generation] Hispanic Americans as ‘Mexicans’ — rather than Americans,” Castro continued. “It’s as if no matter how long you’ve been in this country you’re not ever really an American.”

While America prides itself as a melting pot of cultures and ideals, the assumption that Hispanic Americans are outside American culture — when, in fact, they are a vibrant and important part of it — is a form of erasure. The majority of Hispanic Americans are US-born, not immigrants, but that shouldn’t matter. The implication that a group whose members comprise nearly 60 million Americans, almost one-fifth of the country’s population, are not adequately assimilated exposes a prejudicial false notion of what “American” even means.

Furthermore, the US is a country with no official language and a history of colonization by both English and Spanish speakers; there is a place for both languages among the total hundreds spoken by Americans. Alcindor, who grew up in the famously bilingual city of Miami, replied to Brokaw’s statement by saying that “the idea that we think Americans can only speak English, as if Spanish and other languages wasn’t always a part of America, is, in some ways, troubling.”

Contrary to Brokaw’s statements, a 2016 study from the Pew Research Center found that a majority of Hispanic Americans report either speaking English “very well” or speaking only English at home, altogether. Many Hispanic Americans struggle to retain elements of their ancestral language and culture. Spanish language attrition is a phenomenon that can be attributed, in part, to punitive language policies like those described by Rep. Castro — institutional suppression in the name of “assimilation.”

“Assimilation is denying one culture for the other,” Hugo Balta, National Association of Hispanic Journalists president and senior producer at MSNBC, said in a NAHJ statement in response to Brokaw’s remarks. “Hispanics are no less American for embracing their country of origin or that of their ancestors… being bicultural and bilingual is a strength in an increasingly multi-ethnic, multilingual society.”

After the backlash, Brokaw took to Twitter to apologize, writing, “i [sic] feel terrible a part of my comments on Hispanics offended some members of that proud culture,” before going on about his work reporting on Hispanic issues, how he believes in an “all-sides” narrative, and that he “never intended to disparage any segment of our rich, diverse society which defines who we are.”

(Photo by Mike Coppola/Getty Images)