With grit and determination, these women are taking on the male-dominated building trades.

A Woman's Place: Women in Trades

“A Woman’s Place” is a new series spotlighting the women making bold moves in male-dominated industries.

Construction worker Tranell Rock barely clears five-foot-two in steel-toe work boots. Though she’s 28, she could easily scam her way into a central casting call for high school students if she tried. As she chats with a cluster of hard-hatted coworkers — all of them male, and at least some of whom could be described as “hulking” — Rock is conspicuous in more ways than one.

It takes only a few minutes after arriving at Rock’s midtown Manhattan jobsite to get over the visible differences between her and the men she’s working with. There seems to be an easy rapport between them as they chat over cold water bottles and street vendor hot dogs on their lunch break. Tranell Rock is just another member of the team, doing her part on the construction crew's debris cleanup detail to finish construction on Central Park Tower.

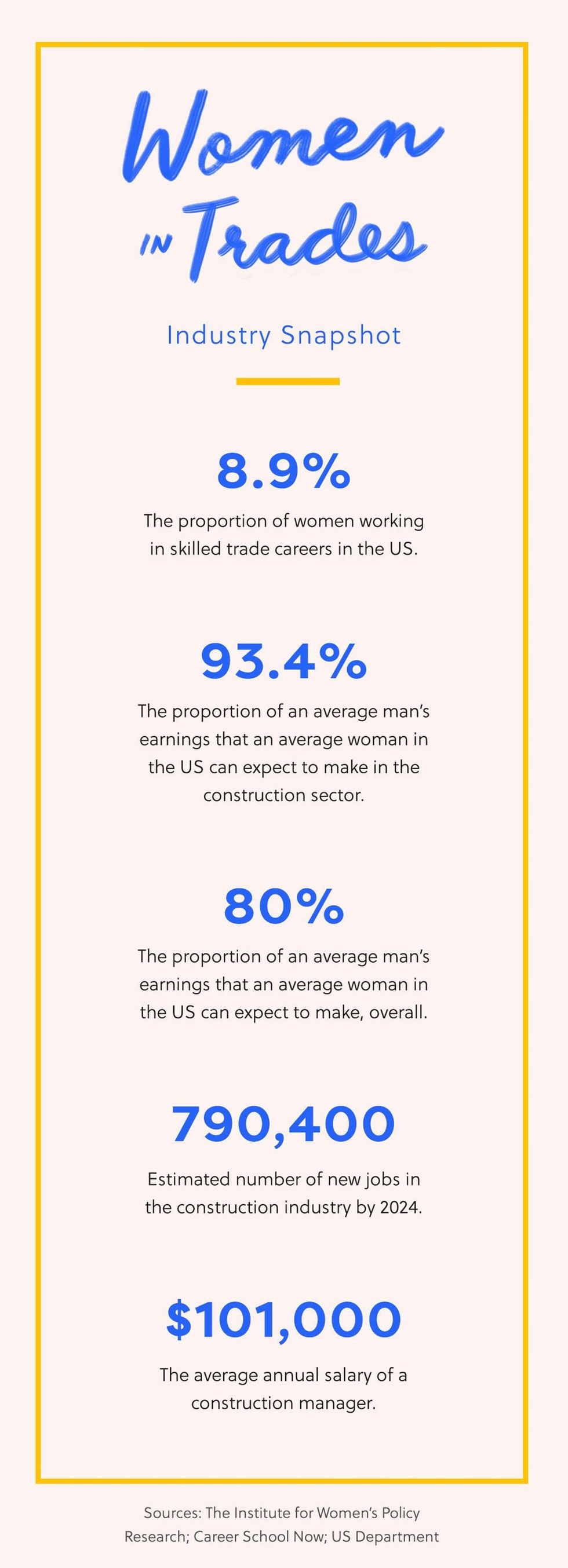

Rock belongs to the estimated 8.9 percent of American women working in the construction and skilled trades industry, according to the US Department of Labor. After getting laid off from a different job in 2012, she took a friend’s advice and applied to a six-week training program to become a union-ready construction laborer. Six years later, she says she hasn’t looked back.

“I come home, and I feel accomplished,” Rock tells us. The work can be physically grueling, but it’s also tangible. She likes working with her hands and helping to create a lasting imprint on the city where she’s spent her whole life. Central Park Tower, once it’s done, will be the tallest skyscraper in New York.

A CHANGING LABOR MARKET

Compared with previous generations, today’s young adults have faced an uphill climb to establish and advance careers in the shadow of the Great Recession. Millions of American jobs were lost between 2008 and 2009, and it wasn’t until April 2014 that total employment across the US reached pre-recession levels. But the future of the US job market remains uncertain, and unless there are major shifts across industries, women will likely fare the worst.

Automation, globalization, and the decline of unions have made it harder to find secure, well-paying jobs with good benefits. For women in the workforce, there are the added concerns of gender-based wage discrimination and the reality that women shoulder a majority of the nation’s student debt burden. Women are also likelier to be among the “precariously” employed, a cohort defined by the International Center for Research on Women as “unemployed; minimum-wage or low-wage workers; part-time, temporary, and contract workers; ‘flexible’ workers; and so-called ‘pink-collar’ and ‘creative’ workers.”

Given the circumstances, it’s easy to see why more and more women in their 20s and 30s might decide to learn a trade. The construction and skilled trades industry has been growing steadily, at an estimated rate of nearly three percent each year, since 2010. US businesses will need to fill 5 million skilled worker jobs by 2020; in response, local labor unions and job training programs across the country are eagerly soliciting prospective students with the promise of debt-free training in exchange for internationally transferable job skills that promise middle-class — or higher — earnings. To meet the steady demand for building sector workers, women are being directly courted to pursue careers as electricians, carpenters, machinists, and other industrial and construction trade professions that have long been considered male domains.

WOMEN HELPING WOMEN

Across the country, gender-segregated vocational training programs offer women safe spaces to learn the skills and expectations of their chosen trades. Tranell Rock is the product of one such program, run by a New York City-based organization called Nontraditional Employment for Women (NEW), which trains and places women in construction, utility, and maintenance careers. Rock tells us that she enrolled in a NEW training program in April 2012; by July of the same year, she was an official member of her local laborers’ union.

Lauren Cardona, 30, recently completed a 13-week apprenticeship readiness training program with a similar organization, Women In Skilled Trades. For those 13 weeks, the Howell, Michigan mother of two drove 45 minutes to and from the WIST training facilities in Lansing, where she and her five classmates — all women — learned about the different specializations available for them to pursue in the building trades, as well as the women-specific health and safety concerns they could encounter on the job. For instance, most safety equipment, such as gloves and hardhats, comes in men’s sizes; thanks to her women-only training program, Cardona knows she will likely have to special order her own gear to ensure it safely fits.

Cardona advises women considering careers in the skilled trades to seek out training programs geared specifically to women.

“It’s been the most helpful thing that I’ve found,” she tells us. “Not only is it women helping women, but the training is specific to women’s issues. And even after we graduate from this, they’re still our advocates while we’re on the job.”

Carpenter Nina MacLaughlin’s professional awakening has a women-helping-women angle of its own, albeit unconventional. MacLaughlin was a staff editor at a Boston newspaper when, just shy of her 30th birthday, she quit.

“I was sick of sitting in front of a screen,” she tells us.

With no backup plan for work, MacLaughlin, on a whim, replied to a Craigslist ad with the heading, “Carpenter’s Assistant: Women strongly encouraged to apply.” The ad had been placed by an older woman carpenter who would become MacLaughlin’s professional mentor, teaching her skill-by-skill on the job. Nearly a decade later, the two women continue to work side by side.

In 2015, McLaughlin published a memoir, Hammer Head: The Making of a Carpenter, that details her career change. She says of the decision: “The satisfaction has been profound.”

EQUAL, BUT NOT THE SAME

Though women maintain a small foothold in the skilled trades, they continue to face certain challenges that their male colleagues simply don’t have to consider. Cardona’s apprenticeship readiness training, for instance, contained an entire unit on how to recognize and report sexual harassment on the job.

Additionally, Cardona, MacLaughlin, and Rock all admit that they’ve felt some pressure to prove themselves in their male-dominated industries just by virtue of being women. MacLaughlin and her mentor have “gotten looks” from men at lumber yards when collecting supplies for jobs; Rock says women in her industry need to “be headstrong” and accept the reality that there will always be men out there who don’t take them seriously. Cardona, who hopes to become accepted into an operating engineer apprenticeship, says she intends to learn how to operate all of the heavy machinery involved in road construction — excavator, crane, bulldozer, and forklift — because she wants to stand out in her field for more than just her gender.

Due to their smaller size and other social factors, women may also approach their jobs differently than men. But this isn’t necessarily a bad thing: Cardona tells us that women tend to have a “lighter touch” when operating machinery, thus ensuring it runs more smoothly.

“We have to work smarter, not harder,” she adds. “A lot of times women bring different ideas [to a job] because we’re not physically as strong.” This need to creatively problem-solve in lieu of brute strength leads women to approach tasks more strategically, which can even get some jobs done faster.

And because women so often have smaller hands than the average man, Cardona says they have an advantage over most men for precision work like pipefitting.

Rock concurs, chuckling that, on most job sites, “I’m definitely the one to go into tiny spaces.”

Gender can even be a selling point on its own merit, as is often the case for MacLaughlin’s home renovation clients. She tells us that most clients will seek her services because she and her colleague are women, not in spite of it. And she’s quick to point out that her interactions with male contractors on construction projects have generally been respectful — contrary to what people might expect.

“With men I worked with at the newspaper, it was way, way more sexist, way more inappropriate… thinking back and thinking about the behavior and the comments and situations, it was so much worse in journalism than it is in the trades,” MacLaughlin says.

PAVING (AND HAMMERING) A FUTURE

Depending on progression and skills, a person working in the skilled trades can expect to earn anywhere from $30,000 a year to well into the six figures. Rock appreciates the financial security: “You work, you go home, and you provide for your family and do what you can for them to have a better life.”

Cardona tells us she wishes she’d considered all her professional options earlier in life, before she’d pursued and completed an associate degree in business.

“I’m proud of it,” she says of her degree, but she admits that the limited professional gains that came from it didn’t match the cost of tuition. In a trade apprenticeship program, training happens on the job: “You earn while you learn.”

Cardona also tells us that she’s proud to be able to show her sons, who are now four and five years old, that girls and women are individuals who are capable of accomplishing everything that boys and men can.

Then there’s the work itself: The satisfaction of making something that people will use every day. MacLaughlin compares the fleeting, self-critical creative work of her parallel life as a writer with the enduring pride that comes from building something like a bookcase, or even a wall, from scratch.

“With carpentry work, we finish up a deck and it’s like, ‘Wow, this is the best deck in the world,’” she tells us. “And that feeling doesn’t go away.”

Cutting the Wires: A Female Electrician Tells All

Julia Wagner Brady tells us about what it's like to change her industry.

Read More